Nuclear Weapons Policy

Editor’s note: This article was published under our former name, Open Philanthropy. Some content may be outdated. You can see our latest writing here.

This is a writeup of a shallow investigation, a brief look at an area that we use to decide how to prioritize further research.

In a nutshell

What is the problem?

Nuclear risks range in magnitude from an accident at a nuclear power plant to an individual detonation to a regional or global nuclear war. Our investigation has focused on the risks from nuclear war, which, while unlikely, would have a catastrophic global impact.

What are possible interventions?

A philanthropist could fund research or advocacy aimed at reducing nuclear arsenals, preventing nuclear proliferation, securing nuclear materials from terrorists, or attempting to more directly prevent the use of nuclear weapons in a conflict (e.g. by working with civil society actors to reduce the risk of conflict). A funder could also raise awareness about risks from nuclear weapons in general by working with media or educators, or through grassroots advocacy.

Who else is working on it?

Several major U.S. foundations fund approximately $30 million/year of work on nuclear weapons issues, with most of this work supporting U.S.-based policy research and graduate/post-graduate education, some advocacy, and “track II diplomacy” (i.e. meetings between nuclear policy analysts and current and former government officials, often from different states). We do not have an estimate of funding from other non-profits in the space, but the Nuclear Threat Initiative has an annual budget of $17-18 million and is not primarily funded by foundations. The U.S., other governments, and the International Atomic Energy Agency spend much larger amounts of money managing risks from nuclear weapons. We see work on nuclear weapons policy outside of the U.S. and U.S.-based advocacy as the largest potential gaps in the field, with the former gap being larger, but also harder for a U.S.-based philanthropist to fill.

What is the problem?

Our focus on nuclear war

There are numerous conceivable scenarios in which some sort of nuclear incident could occur, ranging from a meltdown at a nuclear power plant to the detonation of a “dirty bomb” (i.e. a bomb that combines radioactive material with conventional explosives) to an outright nuclear war between states.[1]George Perkovich, Director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, identified several areas of work that we would classify under the overall rubric of efforts to prevent nuclear war: “The field of nuclear policy includes:

Safety of nuclear power … Continue reading Though this is not a question we have thoroughly investigated, the risk of nuclear war between states strikes us as the most potentially destructive scenario because of the magnitude of some states’ nuclear arsenals, the possibility of wider escalation, and the possibility of nuclear winter. Accordingly, although we recognize the devastating potential of other kinds of nuclear incidents, our discussion below focuses on the risk from nuclear war.[2]George Perkovich, Director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told us that prevention of nuclear war is the nuclear policy area “where there is [likely] the largest scope for philanthropy.” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with … Continue reading Note that we interpret efforts to address the risk of nuclear war broadly, to include issues like reduction of nuclear arsenals, prevention of nuclear proliferation, securing nuclear materials, and facilitating domestic civil discourse regarding nuclear weapons among countries that may seek to acquire nuclear weapons.

The U.S. and Russia hold the vast majority of the world’s nuclear weapons:[3]We do not have a detailed understanding of the methodology of these estimates. But, when searching the literature on this topic, we gathered the impression that Kristensen and Norris produce commonly-cited estimates that are updated annually. Other estimates we saw were very similar. Kristensen … Continue reading

| COUNTRY | ESTIMATED NUCLEAR WEAPONS INVENTORY |

|---|---|

| Russia | 8,000 (4,300 in military custody) |

| United States | 7,300 (4,760 in military stockpile, 1,980 deployed) |

| France | 300 |

| China | 250 |

| Britain | 225 |

| Pakistan | 100-120 |

| India | 90-110 |

| Israel | 80 |

| North Korea | <10 |

| Total | ~16,300 |

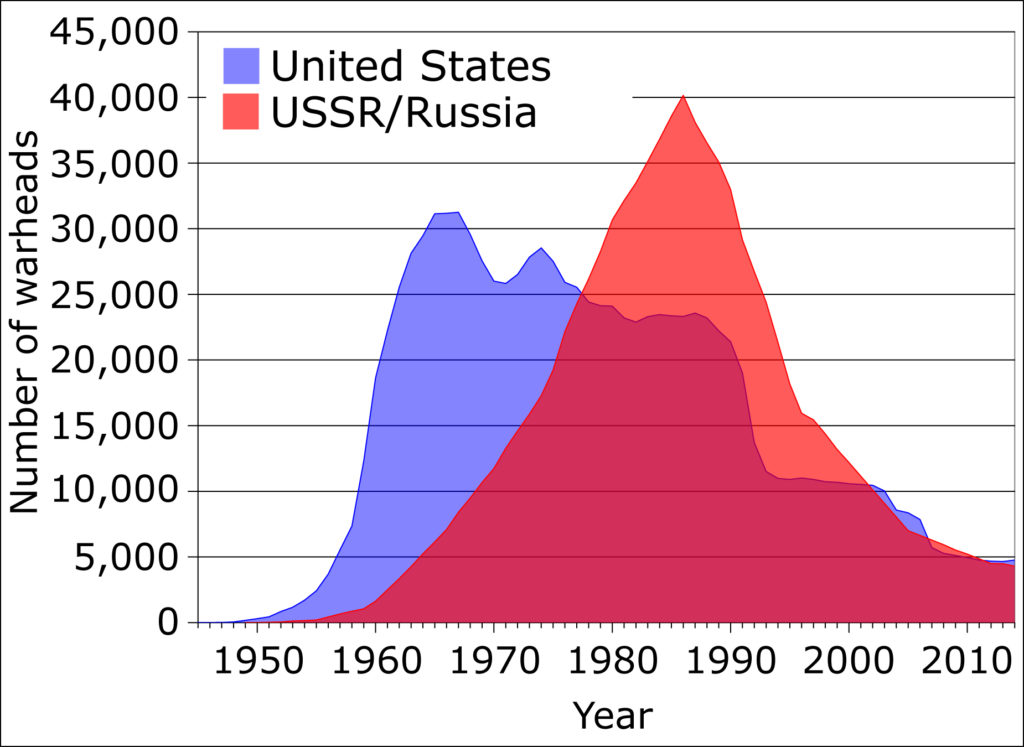

Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. and Russia nuclear weapons inventories have greatly (and fairly continuously) declined, as illustrated by the graph below:[4] Figure: Wikimedia Commons, US and USSR nuclear stockpiles. Data from Kristensen and Norris 2013, pg 78, Figure 2.

We have not thoroughly investigated the probability or likely consequences of a nuclear detonation or a broader nuclear war, though we see both scenarios as possibilities. Our understanding is that the risk of global nuclear escalation has decreased substantially since the end of the Cold War.[5]“As reflected by its large funding share, concern about nuclear weapons arms control and nonproliferation has been a mainstay of the field — and of the Peace and Security Funders Group — for the past two decades. Although the danger of a nuclear war engulfing the planet receded dramatically … Continue reading We note, however, that some people we spoke with suggested that total nuclear risk had increased since the Cold War.[6]“Nuclear weapons pose a serious global threat but nuclear security is no longer a high profile issue. Ms. Gregory believes the issue needs be revisited because nuclear weapons pose a greater threat now than during the Cold War.” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Erika … Continue reading

Which conflicts are most worrisome?

Though very unlikely in the present climate, a nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia would have the greatest destructive potential. A 1979 report by the U.S. Office of Technology Assessment estimated that in an all-out nuclear war between the U.S. and Russia, 35-77% of the U.S. population and 20-40% of the Russian population would die within the first 30 days of the attack.[7]“In order to examine the kind of destruction that is generally thought of as the culmination of an escalator process, the study looked at the consequences of a very large attack against a range of military and economic targets. Here too calculations that the executive branch has carried out in … Continue reading We have not vetted this estimate, but note that at the time, combined U.S./Russia nuclear weapons stockpiles were approximately three times as large as they are today, as seen in the graph above. An additional potential risk of a U.S./Russia nuclear would be the nuclear winter that might follow. Nuclear winter could potentially disrupt global food production and result in an even larger number of deaths, though we have not thoroughly explored the likelihood or likely consequences of this scenario.

People we spoke with generally perceived the greatest risk of nuclear conflict in South Asia, where Pakistan has pledged to respond to any Indian attack on its territory with a nuclear bomb.[8]“Dr. Perkovich believes that the highest risk of nuclear war stems from conflict in South Asia. If there were another terrorist attack on a major Indian city that could plausibly be linked to Pakistan, there is a significant chance that India would respond with a conventional military attack on … Continue reading Some scholars have argued that a war between India and Pakistan could alter the global climate, potentially threatening up to a billion people with starvation,[9]“Most cities and countries have stockpiled food supplies for just a very short period, and food shortages (as well as rising prices) have increased in recent years. A nuclear war could trigger declines in yield nearly everywhere at once, and a worldwide panic could bring the global agricultural … Continue reading though this estimate strikes us as high. Our understanding is that this claim is primarily based on:

- Modeling the amount of smoke that would reach the stratosphere in the event of a nuclear war between India and Pakistan in which 100 nuclear weapons strike cities.[10]“We assess the potential damage and smoke production associated with the detonation of small nuclear weapons in modern megacities…. We analyze the likely outcome of a regional nuclear exchange involving 100 15-kt explosions (less than 0.1% of the explosive yield of the current global nuclear … Continue reading

- Using a climate model to simulate the effect of that smoke going into the stratosphere.[11]“We use a modern climate model and new estimates of smoke generated by fires in contemporary cities to calculate the response of the climate system to a regional nuclear war between emerging third world nuclear powers using 100 Hiroshima-size bombs (less than 0.03% of the explosive yield of the … Continue reading

- Using a crop model to estimate the effect of those climactic changes on the yields of crops in China and the Midwest.[12]“A regional nuclear war between India and Pakistan could decrease global surface temperature by 1 to 2°C for 5 to 10 years, and have major impacts on precipitation and solar radiation reaching Earth’s surface. Using a crop simulation model forced by three global climate model simulations, we … Continue reading

The last paper cited estimated that a 100-weapon nuclear exchange between India and Pakistan would result in a 10% decline in average caloric intake in China, with potentially similar consequences elsewhere.[13]“Taken together, the declines in rice, maize, and wheat would lead to a decline of more than 10% in average caloric intake in China. However, this is the average effect, and given the great economic inequality seen in China today the impact on the billion plus people in China who remain poor … Continue reading

We have not vetted this analysis. However, even accepting its conclusions, our impression is that relatively little work has been done to consider the likely human consequences of the subsequent decline in agricultural production.[14]Most of the reasoning seems to come in a few paragraphs in the paper previously cited:

“With a large reduction of agriculture production after a regional nuclear war, countries would tend to hoard food, driving up prices on global grain markets. As a result the accessible food, the food that … Continue reading We would guess that the predicted loss of crops would be insufficient to cause a billion people to starve for the following reasons:

- China has significant food reserves, which, according to the paper estimating changes in the yields of crops cited above, would not be depleted until two years after the initial nuclear exchange.[15]“In addition, expressed as days of food consumption, China has significantly larger reserves of grain than the world as a whole. In the summer of 2013, wheat reserves totaled nearly 167 days of consumption, and rice reserves were 119 days of consumption [Foreign Agricultural Service, … Continue reading

- Our impression is that the crop model was not designed with extreme scenarios like this in mind, and is not accounting for pressure to make significant changes to food production in the midst of a global crisis.

- A substantial portion of crops grown are used to feed livestock, which is significantly less efficient than slaughtering existing livestock and directly eating the food we normally use to raise them. In the short run, livestock reserves could be slaughtered to meet demand for food.[16]“Livestock producing milk, meat, eggs, and so forth typically consume multiple calories in feed for each calorie of animal product provided for human consumption, in addition to other costs. So in a world with a severe rise in food prices or tight non-price rationing of food reserves, they would … Continue reading In the longer run, we would guess that a decrease in the food supply would raise food prices, creating incentives to produce more food (e.g. by using more land for food production and shifting away from less efficient animal-based means of production).

What are possible interventions?

Areas for nuclear policy work

Almost any kind of progress on nuclear security ultimately requires some kind of change on the part of government, or the prevention of some change. Accordingly, much of the grant-making in this field focuses on:

- Policy analysis by think tanks and university centers focused on nuclear weapons issues.

- Advanced education to create better policy analysis in the future, such as support for academic centers that provide graduate and post-doctoral training in the field of nuclear weapons policy.[17]“Advanced Education Effective policymaking on nuclear security matters requires the best advice from diverse fields including the natural and social sciences, nuclear industry, and policy world, among others. It also entails public debate, which takes different forms in different countries but is … Continue reading

- Advocacy and communications, which is a major focus of the Ploughshares Fund (discussed below).

- Track II diplomacy—meetings between nuclear policy analysts and current and former government officials, often from different states.

George Perkovich, Director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, identified several different goals for this work:[18]“The field of nuclear policy includes: Safety of nuclear power plants Prevention of nuclear war Prevention of accidental discharge of weapons Reduction of nuclear arsenals Prevention of nuclear weapon proliferation, including to terrorists” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation … Continue reading

- Reduction of nuclear arsenals

- Prevention of nuclear proliferation

- Preventing terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons

- Direct efforts to prevent nuclear escalation

Additionally, work can be categorized by the region the topic relates to (e.g. policy related to Iran, Russia, South Asia, North Korea, United States) and where the work is done (e.g. is the scholar/advocate working in the U.S. or India?).

Reduction of existing nuclear arsenals

Work to reduce nuclear arsenals typically focuses on the five permanent members of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, which possess the largest numbers of nuclear weapons. Several approaches have been proposed for encouraging these countries to reduce their nuclear arsenals:

- Laying the intellectual groundwork for further talks between the U.S. and Russia about reducing the number of warheads in each country’s stockpile

- Advocating for the U.S. executive branch to reduce the U.S. nuclear stockpile[19]Communication and public engagement: Increased support among the elite public for reduction in number of U.S. nuclear weapons and improved nonproliferation policies U.S.-Russia: Commit not to develop new nuclear weapons; avoid production and deployment of new heavy intercontinental ballistic … Continue reading

- Supporting policy research and advocacy related to ballistic missile defense. Russia and China are concerned that U.S. investment in ballistic missile defense—i.e. systems for shooting down incoming ballistic missiles—could destabilize deterrence relationships. If ballistic missile defense were sufficiently effective, it could increase the number of nuclear weapons needed to ensure successful retaliation. Accordingly, U.S. investment in this area poses a potential obstacle to negotiating further arms reductions in Russia and China.[20]“The US is currently engaging in the development of ballistic missile defense (BMD), a platform to intercept intercontinental ballistic missiles mid-flight. This may be an obstacle to reduced nuclear arsenals and is a source of concerns for Russia and China. Though BMD theoretically could provide … Continue reading

Some organizations, such as Global Zero, advocate for the elimination of all nuclear weapons. We have not investigated the question of whether outright elimination is likely to be the best policy path, but we understand this to be an area of active debate within the academic community.[21]“Most people who think about and work on nuclear proliferation — the spread of nuclear weapons to new countries — think it’s a problem. Nukes are hugely destructive weapons, proliferation is thought to increase the odds they’ll be used, and it’s worth working very hard to prevent them … Continue reading

The Ploughshares Fund is the largest funder of advocacy efforts with an annual budget of approximately eight million dollars. It argues in favor of cutting the U.S. federal budget for nuclear weapons.[22]“It’s clear, however, that the Senate just made a bold move to cut one of the United States’ most wasteful nuclear programs. It’s an action that Ploughshares Fund and its grantees have been working to achieve. It’s also a strong signal that the days of unlimited nuclear weapons spending … Continue reading Joe Cirincione (President, Ploughshares Fund) and Philip Yun (Executive Director, Ploughshares Fund) identified the following advocacy opportunities for reducing the size of nuclear stockpiles in the U.S.:

- Promoting public support for the ideas that nuclear weapons continue to pose significant risks, have limited deterrence value, and are costly to maintain. A philanthropist could seek to build support for these ideas by working with filmmakers or improving online educational materials and social media campaigns.

- Supporting efforts to revive the U.S.-Russia dialogue on nuclear weapons.

- Seeking to influence the nuclear policy of the next presidential candidates by supporting relevant policy analysis.[23]“Influencing public opinion A small portion of American citizens currently see our large nuclear arsenal as an important national security asset. But maintaining such a large arsenal has limited utility in meeting today’s national security challenges. Moreover, nuclear issues are getting far … Continue reading

- Advocating for lawmakers to reduce the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

- Supporting policy analysis and advocacy opposing the development of ballistic missile defense in the U.S. in hopes of making U.S.-Russia and U.S.-China mutual arms reductions more likely (discussed above).

While arms reductions in the U.S. and Russia may appear to be a natural target for a funder interested in reducing global catastrophic risk, we are uncertain about how much additional philanthropy could assist with arms reduction at this time. As noted above, the U.S./Russia weapons inventories have steadily declined since the end of the Cold War, suggesting that progress on the problem may continue in the absence of additional philanthropy. In addition, people we spoke with and consultants surveying the field for other funders saw limited opportunities for additional philanthropy to push forward U.S./Russia arms reductions.[24]“The U.S. and Russia are big players in any discussion of nuclear weapons and have already made significant reductions in nuclear weapons since the Cold War. While continuing to reduce nuclear weapons is desirable, the current political tensions between the U.S. and Russia make another round of … Continue reading

Prevention of nuclear proliferation

Non-proliferation work is focused on preventing additional countries from obtaining nuclear weapons. Within non-proliferation, the most common concern among people we spoke with was that Iran might obtain a nuclear weapon. For example, Joe Cirincione suggested that a philanthropist could advocate in favor of making a deal with Iran that would prevent Iran from obtaining nuclear weapons,[25] “A philanthropist could support the following policy changes in the US: […] Support a deal with Iran that prevents that nation from getting nuclear weapons.” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Joe Cirincione, November 15, 2014. which is a major focus for the Ploughshares Fund (see “Philanthropic Funders” below). If Iran obtains nuclear weapons, it could potentially destabilize the Middle East and encourage other countries to obtain nuclear weapons.[26]“The possibility that Iran might obtain a nuclear weapon is also a major area of concern in the sector, not so much in terms of the potential for actual detonation of a weapon (since Iran doesn’t currently have a weapon), but because of the geopolitical implications if Iran were to go nuclear. … Continue reading In early 2015, after most of this review was already written, the U.S. and Iran reached an agreement on a framework for monitoring Iran’s nuclear program, though the deal has not yet been approved. We have a limited understanding of how this might affect philanthropic approaches related to non-proliferation in Iran.[27]“International negotiators assembled in Switzerland have announced the broad terms of the Iranian nuclear deal. Here they are, based on what we know, translated into plain English.

An important note: the deal is not yet finalized, and it is not particularly detailed. Thursday’s announcement is … Continue reading

Some funders appear to focus on advocacy to individual countries that may attempt to acquire nuclear weapons, or on funding academic and civil discourse related to nuclear weapons in key regions through non-nuclear states such as Turkey, Brazil and South Korea.[28] Hewlett Foundation Nuclear Security Initiative Logic Model. Others focus more on supporting international institutions such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).[29] “Carnegie Corporation focuses on a more effective IAEA by working with the US and moderate NAM countries and the IAEA Board of governors.” Redstone Strategy Group 2012, pg 26. Carl Robichaud—a Program Officer focusing on the International Peace and Security Program at the Carnegie Corporation of New York—identified the following options for a philanthropist to support the IAEA:[30] GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Carl Robichaud, October 14, 2014.

- Fund open source analysis on topics that would be of use to the IAEA

- Hold workshops where IAEA staff can learn how to utilize new tools and approaches, such as geospatial analytics and big data analysis (the Carnegie Corporation put on a workshop between IAEA staff and innovators from other sectors in December)

- Support the Vienna Center for Disarmament and Non-Proliferation, which serves as research and training center for the IAEA

- Sponsor dialogues within the IAEA to reduce politicization

Preventing terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons

Another approach would be to support appropriate monitoring of existing nuclear material in an attempt to prevent it from falling into the hands of terrorists. The difficulty and high costs of manufacturing nuclear weapons makes securing nuclear materials important for preventing nuclear terrorism.[31]“NTI’s chief focus is securing nuclear materials from falling into terrorist hands. It is very costly to manufacture nuclear materials such as plutonium and highly enriched uranium. These costs exceed what terrorists can afford. Therefore, preventing terrorists from acquiring nuclear materials … Continue reading The Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI) has been addressing this problem by using the Nuclear Security Summits to develop buy-in for global, enforceable nuclear security standards, which currently don’t exist.[32]“There is no global, enforceable standard for securing nuclear materials.

A series of nuclear summits have taken place over the past five years:

The US hosted one in 2010

South Korea hosted one in 2012

The Hague hosted one in 2014

A fourth is scheduled for 2016, in the US, hosted by President … Continue reading

A nuclear terrorist attack is not a nuclear war and therefore not directly in the center of this investigation, but we would guess that nuclear terrorism—particularly in South Asia—could potentially ignite a nuclear war. A philanthropist could try to prevent terrorists from obtaining nuclear weapons through:

- Policy development and advocacy related to creating a standard set of international norms regarding the security of nuclear materials.[33]“There is no global, enforceable standard for securing nuclear materials. A series of nuclear summits have taken place over the past five years: The US hosted one in 2010 South Korea hosted one in 2012 The Hague hosted one in 2014 A fourth is scheduled for 2016, in the US, hosted by President … Continue reading

- Funding innovative demonstration projects in hopes of causing governments to scale them up. For example, Joan Rohlfing —President and COO of NTI—told us that the Nuclear Threat Initiative worked with Serbia to return non-secure nuclear materials to Russia, and that the effort led to the creation of a U.S. government program that spent billions of dollars on similar projects.[34]“NTI sometimes funds demonstration projects that get scaled up by governments. For example, with help from the U.S. government, NTI worked with Serbia to return non-secure nuclear materials to Russia. This effort led to the creation of a U.S. government program called the Global Threat Reduction … Continue reading

Our impression is that the security of nuclear materials already receives significant attention. It is the primary focus of the Nuclear Threat Initiative,[35]“NTI’s chief focus is securing nuclear materials from falling into terrorist hands. It is very costly to manufacture nuclear materials such as plutonium and highly enriched uranium. These costs exceed what terrorists can afford. Therefore, preventing terrorists from acquiring nuclear materials … Continue reading and a priority for national governments.[36]“Dr. Perkovich believes that the risk of a nuclear attack by terrorists is generally exaggerated, though he remains unsure of this view because there are people he trusts who tell him he is wrong about this.[…] Governments are very much on top of this risk and it is unlikely that there is any … Continue reading

Direct efforts to prevent nuclear war

Direct efforts to prevent nuclear war may focus on attempting to reduce the likelihood of deployment of nuclear weapons in a given conflict situation, or on attempting to reduce the risk of conflict between nuclear states. In our conversation, Dr. Perkovich gave some examples of both kinds of efforts with respect to India and Pakistan, focusing on various forms of civil society engagement, “track II” diplomacy, and policy research.[37]“Examples of efforts to reduce the risk of a nuclear detonation in South Asia include:

Meetings between leaders and former leaders of both sides, diplomats, and experts in the field of nuclear conflict resolution to come up with ideas for how to build trust between the two countries and between … Continue reading

We have not thoroughly explored this area, but people we spoke with have suggested there may be limited potential for additional philanthropy to address these issues, at least in Russia (as discussed above) and in South Asia.[38]“The use of nuclear weapons by India or Pakistan is seen by many in the sector at the most tangible area of short-term concern. An exchange of nuclear weapons between the two countries or an unauthorized or accidental use of weapons in the region would be catastrophic. However, there are limited … Continue reading

Approaches to improving nuclear weapons policy and their track records

Policy analysis and advanced education

A majority of funding supports policy research and advanced education, especially from the large foundations in this space.[39]“Foundations supported a variety of strategies, but Policy Analysis and Research received nearly half of all funds.

About 47 percent of the funds — or over $120 million — recorded in the database [on peace and security funding] supported work that was intended for Policy Analysis and … Continue reading However, we have a fairly limited sense of the track record of policy analysis for improving nuclear weapons policy. Nevertheless, we understand that funding from the Carnegie Corporation and the MacArthur Foundation is generally believed to have played a major role in the passage of the Nunn-Lugar Act[40]“There are several different versions of such an impact in this case. The most obvious is the fact that foundation-funded research and a foundation-funded report—“Soviet Nuclear Fission: Control of the Nuclear Arsenal in a Disintegrating Soviet Union,” produced by a Prevention of … Continue reading, which was responsible for “the dismantling or elimination of 7,514 nuclear war-heads, 768 ICBMs, 498 ICBM sites, 155 bombers, 651 submarine-launched ballistic missiles, 32 nuclear submarines, and 960 metric tons of chemical weapons.”[41] Nunn-Lugar Report for GiveWell’s History of Philanthropy Project by Benjamin Soskis, July 2013 (DOCX), pg 1. For context, according to one estimate, the U.S. and Russia held 19,008 and 29,154 nuclear weapons (respectively) when the Nunn-Lugar Act was passed in 1991, so that Nunn-Lugar was responsible for eliminating or dismantling approximately 15% of the total U.S./Russia nuclear arsenal.[42] See Kristensen and Norris 2013, pg 78, Figure 2, year 1991.

Policy research funded by philanthropists may have played a role in improving nuclear policy in a few other cases besides the Nunn-Lugar Act—such as establishing theories of deterrence and the New START treaty, which further reduced deployed warheads in the U.S. and Russia.[43]“Over the last fifty years, philanthropy has played an influential role in several nuclear policy advances, such as:

Establishing of a theory of deterrence – in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, research at universities, non-governmental organizations, and think tanks lead to theories of deterrence … Continue reading

Due to our limited understanding of nuclear weapons policy analysis, we also have a limited understanding of the potential impact of advanced education on nuclear weapons policy.

Advocacy

Multiple people suggested to us that work on advocacy and communications is relatively neglected in nuclear weapons policy.[44]“Because governments control nuclear weapons, most philanthropic work tries to inform or influence government actions and policy regarding nuclear weapons. A big portion of philanthropic money goes into technical and policy research on nuclear issues. Communications gets fairly limited funding … Continue reading Our investigation therefore focused more closely on opportunities within advocacy.

In addition to the advocacy opportunities already mentioned (especially under the heading “Reduction of existing nuclear arsenals”), building general capacity for advocacy in order to change policy if a window of opportunity arises may be valuable.[45]“It is unlikely that the public will ever care about nonproliferation and disarmament to the extent that it did during the Cold War or that nuclear security can become a broad-based constituency-driven issue. However, a well-run communications and advocacy campaign might develop a public base of … Continue reading

We are uncertain about the role for grassroots advocacy on nuclear weapons issues, in comparison with more technocratically-oriented advocacy and policy analysis. On this topic:

- Robert Einhorn—a senior fellow with the Arms Control and Non-Proliferation Initiative and the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at the Brookings Institution—cautioned that grassroots efforts have a mixed record at best in changing nuclear policy, pointing to the fact that the U.S. has not ratified the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty despite its support from a large majority of Americans.[46]“Mr. Einhorn does not believe grassroots advocacy on nuclear weapons issues has often been very effective. At best, its record has been mixed. For example, despite significant public support for the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, the Senate voted it down during the Clinton presidency. On … Continue reading

- Mr. Robichaud pointed to the New START treaty as an instance where public engagement played an important role.[47]“Generating public engagement was integral to the success of the New START treaty. Public opinion will likely be influential in the future as well. It is important to build an advocacy infrastructure to ensure that organizations can engage the public when the right moment occurs.” GiveWell’s … Continue reading

Philanthropic opportunities in other countries

Very little foundation funding supports nuclear policy work abroad, which means that other countries have much more limited capacity for developing and advocating for policy related to nuclear weapons,[48]“The US has a far broader base of expertise on nuclear issues than most other countries do. It could be effective to contribute to the development of policy schools and think tanks internationally that would address nuclear issues, especially in the major countries that have nuclear weapons. The … Continue reading though U.S. foundations have funded some policy research in Russia and Asia:

- The MacArthur Foundation’s Asia Security Initiative supported increased communication and dialogue between policy analysts working on security issues relevant to Asia, including supporting researchers in Asia. This program has since ended.[49]“Asia Security Initiative Policy Research MacArthur ended the Asia Security Initiative in December, 2014. The Foundation is proud of the increased communication and dialogue its Asia Security Initiative has sparked between policy experts, and encouraged to see the work of its grantees being used … Continue reading

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has a satellite center in Moscow, and it has received funding from the Carnegie Corporation.[50]“Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, DC For the Carnegie Moscow center in support of the endowment’s global vision. 36 Months, $1,500,000. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (the Endowment) is a global think tank with a mission to contribute to global security, … Continue reading

A philanthropist looking to further support opportunities in other countries could:

- Fund the creation of a center for nuclear policy research in Pakistan in hopes of increasing Pakistan’s willingness to comply with international nuclear law and norms.[51]“Creating a center of excellence on nuclear safety in Pakistan to highlight Pakistan’s strong record on nuclear safety, as a way to boost Pakistan’s confidence and buy-in to the international system. The idea is that such buy-in would increase Pakistan’s willingness to comply with … Continue reading

- Fund fellows programs for people from Asia, perhaps including an exchange component during which the fellows spend time at U.S. or U.K. institutions, to train the next generation of nuclear policy analysts.[52] Based on materials from conversations not documented in public notes.

- Fund professors/senior researchers from U.S. nuclear policy institutions to visit think tanks in Asia and help train young nuclear policy analysts.[53] Based on materials from conversations not documented in public notes.

However, people we spoke with suggested it would be challenging for a foundation to make its first grants on nuclear weapons policy in support of programs abroad[54]“While investing in foreign projects may yield larger returns, Mr. Robichaud would not recommend that a new funder begin its work by funding overseas policy research. Given the political and social complexities, it is much more difficult to develop an effective giving strategy. For example, it is … Continue reading and stressed the importance of having a local presence for monitoring grants.[55] “It is expensive to fund policy and advocacy work in South Asia, in part due to India’s size. However, to properly monitor and evaluate effectiveness of grants, it is best to have a local presence.” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Philip Yun, October 16, 2014. Our impression is that a philanthropist supporting research, education, and/or advocacy abroad would face significant challenges in terms of networking, communication, understanding context, and monitoring/evaluation.

We distinguish between work done in other countries and work about the policies of other countries. While the former receives limited attention, the latter does not, and has been discussed in various contexts above. For example, work related to potential conflict in South Asia—where the greatest threat is perceived[56]“Dr. Perkovich believes that the highest risk of nuclear war stems from conflict in South Asia. If there were another terrorist attack on a major Indian city that could plausibly be linked to Pakistan, there is a significant chance that India would respond with a conventional military attack on … Continue reading—is relatively crowded. Nuclear issues in South Asia receive substantial attention in the form of programs at universities and think tanks[57]“Many universities and think tanks have well-known programs related to South Asia. These programs in part aim to promote dialogue between groups and elites within both countries. The popularity of South Asia policy studies may be related to how potentially dangerous the region is from a nuclear … Continue reading as well as track II diplomacy, and some funders see little room for additional philanthropy on the topic.[58]“The use of nuclear weapons by India or Pakistan is seen by many in the sector at the most tangible area of short-term concern. An exchange of nuclear weapons between the two countries or an unauthorized or accidental use of weapons in the region would be catastrophic. However, there are limited … Continue reading

Who else is working on this?

Government

According to Gary Samore, Executive Director for Research at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard:[59] GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Gary Samore, September 8, 2014

Nearly all government security agencies are involved with nuclear policy to some degree, including:

- The White House International Security Council

- The Department of Defense

- The Department of State

- The Department of Energy, involved in both nuclear energy and nuclear security (through the National Nuclear Security Administration)

- Intelligence agencies

We have not investigated the amount of funding these agencies devote to nuclear issues and have a limited understanding of their activities. But some agencies with large budgets focus primarily on keeping people safe from nuclear weapons:

| AGENCY | BUDGET | ACTIVITIES |

|---|---|---|

| National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) | $12.6B, of which $1.9B is categorized as non-proliferation.[60]“Delivered to Congress today, the FY 2016 President’s budget request for the NNSA of $12.6 billion represents an increase of $1.2 billion or about 10.2 percent over the FY 2015 appropriations level. It supports key Department of Energy and NNSA priorities including: effective stewardship of the … Continue reading | “NNSA maintains and enhances the safety, security, reliability and performance of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile without nuclear testing; works to reduce global danger from weapons of mass destruction; provides the U.S. Navy with safe and effective nuclear propulsion; and responds to nuclear and radiological emergencies in the U.S. and abroad.”[61] National Nuclear Security Administration, About us |

| Domestic Nuclear Detection Office (DNDO) | $304M[62] Department of Homeland Security, Budget-in-Brief: FY 2015 pg 7, table. | The DNDO coordinates U.S. government efforts to detect and prevent nuclear and radiological terrorism against the United States.[63]“DNDO works to protect the Nation from rad/nuc terrorism by developing, acquiring, and deploying detection technologies, supporting operational law enforcement and homeland security partners, and by continuing to integrate technical nuclear forensic programs and advancing the state-of-the-art in … Continue reading |

In addition, some intergovernmental organizations devote substantial funding to nuclear security issues. For example, in 2014, the International Atomic Energy Agency had a budget of €344M.[64] IAEA Regular Budget for 2014 See table.

We currently have a very limited understanding of the activities of these U.S. government agencies and the IAEA. However, our understanding is that the government provides at most limited support for the primary areas addressed by philanthropic funders, such as policy development, advanced education, advocacy, and track II diplomacy.[65] “The US government spends very little on nuclear policy development or education on nuclear issues, and these areas may be effective options for philanthropic funding.” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Gary Samore, September 8, 2014.

Philanthropic funders

A 2012 report by Redstone Strategy Group, commissioned by the Hewlett Foundation, estimated that philanthropic funding for work on nuclear security between 2010 and 2012 was $31 million/year.[66] Redstone Strategy Group 2012, pg 5.

Our impression is that the total funding in the field has not substantially changed, though some funders have exited the field. A few foundations account for the vast majority of this funding.

| FUNDER | BUDGET (2014 ESTIMATE) | FOCUS AREAS |

|---|---|---|

| MacArthur Foundation | ~$10M[67] “The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation – also provides approximately $10 million annually to nuclear issues.” GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Carl Robichaud, October 14, 2014. | Policy research and advanced education in the U.S., focused on control of fissile materials and preventing the spread of nuclear weapons to terrorists.[68]Under the heading “What We Fund,” a MacArthur Foundation document lists policy research and advanced education, with the following descriptions: “Policy Research The Foundation focuses on preventing nuclear terrorism by denying terrorists access to fissile materials—highly enriched uranium … Continue reading |

| Carnegie Corporation of New York | ~$10M[69] “The Carnegie Corporation of New York – provides approximately $10 million annually to nuclear issues. GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Carl Robichaud, October 14, 2014. | Policy research, advanced education in the U.S., track II diplomacy. Focused on arms reductions, non-proliferation, and security of nuclear materials.[70]“Nuclear weapons remain one of the greatest threats to global security. We seek to reduce this threat by investing in cutting edge analytical work on nonproliferation, supporting education and training programs for the next generation of nuclear experts, and supporting a limited number of Track … Continue reading |

| Ploughshares Fund | ~$8M, ~$5.5M in grants | Advocacy, especially U.S. policy towards Iran and the U.S. nuclear budget.[71]“Ploughshares is an operating foundation with a Washington policy focus and an annual budget of around $8 million, about $5.5 million of which is spent on grants[…] Currently, Ploughshares Fund is focused on U.S. policy toward Iran and rightsizing the U.S. nuclear budget.” GiveWell’s … Continue reading |

| Hewlett Foundation | Previously $4M (2012 estimate),[72] Redstone Strategy Group 2012, pg 8, figure 3. “Note that exact annual budgets are difficult to calculate due to multi-year grants and multi-project grants.” exiting the field.[73] “The Hewlett Foundation is in the process of winding down its Nuclear Security Initiative in 2014 and is no longer accepting grant applications.” Hewlett Foundation Nuclear Security Initiative Webpage. | Security of nuclear materials and reducing nuclear arsenals.[74]“[…]the Hewlett Foundation began a short term initiative in 2008 to explore ways to help reduce the risk of nuclear disaster. The Hewlett Foundation’s strategy focuses on finding ways to reduce nuclear arsenals, and recognizes that the United States and emerging power countries must work … Continue reading Hewlett’s largest grants in this field were to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and the Ploughshares Fund.[75] See search results of the Hewlett Foundation Grants Database within the nuclear security program, sorted by amount. Hewlett Foundation Grants Database, 2015. |

| Sloan Foundation | Previously $2.9 million (2012 estimate),[76] Redstone Strategy Group 2012, pg 8, figure 3. “Note that exact annual budgets are difficult to calculate due to multi-year grants and multi-project grants.” exited the field.[77] Based on material from conversations that is not documented in public notes. | Policy research and advanced education.[78] Based on material from conversations that is not documented in public notes. |

| Skoll Global Threats Fund | $1-2M | Advocacy, especially U.S. policy toward Iran. Ploughshares is a major grantee.[79]“The Skoll Global Threats Fund provides $1-2 million/year on nuclear security issues, with its primary focus a peaceful resolution to the Iran nuclear threat. Its work on nuclear weapons is more focused on advocacy than policy research, and it has been of the larger institutional funders of … Continue reading |

| Stanton Foundation | $2.3M (2012 estimate)[80] Redstone Strategy Group 2012, pg 8, Figure 3 | Advanced education and policy research in the U.S.[81]The Stanton Foundation website lists two areas for grants under its International and Nuclear Security Program Area: “Course Development Program The Foundation’s only open application grant opportunity in this area is for faculty who wish to develop new undergraduate courses in nuclear issues. … Continue reading |

There are also some nonprofits that work on nuclear security issues that do not receive most of their funding from foundations, including, most notably, the Nuclear Threat Initiative (NTI), whose 2015 budget is about $17-18M. Of this, about 90% is devoted to nuclear weapons and about 30% is granted to other organizations (though NTI’s grants usually resemble contracts for service with partners who carry out specific projects that NTI has designed).[82]“NTI’s annual budget is around $17 to $18 million, but its expenses are closer to $15 million. Each year, NTI raises all the money it needs to operate. NTI used to allocate roughly 70% of its budget to nuclear and 30% to biological threats, with occasional work on chemical threats. Recently, it … Continue reading Within nuclear weapons policy, NTI primarily emphasizes securing nuclear materials in order to prevent terrorism, with non-proliferation as a secondary emphasis.[83]“NTI’s chief focus is securing nuclear materials from falling into terrorist hands. It is very costly to manufacture nuclear materials such as plutonium and highly enriched uranium. These costs exceed what terrorists can afford. Therefore, preventing terrorists from acquiring nuclear materials … Continue reading We do not have an overall accounting of activity by other nonprofits in this area, but a list of the top grant recipients in peace and security in 2008-2009 is available in a report by the Peace and Security Funders Group.[84] See Peace and Security Funders Group 2011 pg 22, Table 11. We would guess that many of the major nonprofits working on nuclear weapons policy are listed there.

Foundations also provide substantial funding for peace and security that isn’t explicitly classified as work on nuclear weapons policy. According to the Peace and Security Funders Group, in 2008-2009, 91 U.S. foundations gave a total of $257M to promote peace and security, for an average of about $130M per year.[85]“Ninety-one American foundations made commitments to invest a total of $257,221,598 in civil society efforts to promote peace and security over the two year period of 2008 and 2009. The total in 2008 was $136,403,719 and the total in 2009 was $120,817,878.” Peace and Security Funders Group … Continue reading The largest focus areas for these funders (measured by dollars granted) were:

- Controlling and Eliminating Weaponry (which is described as “mainly focused on nuclear weapons”)

- Prevention and Resolution of Violent Conflict

- Promoting International Security and Stability

Each of these areas received about 20-30% of the total funding.[86]“Controlling and Eliminating Weaponry — mainly focused on nuclear weapons — is the primary concern (as measured in dollars) of funders in the field, followed closely by Prevention and Resolution of Violent Conflict and Promoting International Security and Stability.” Peace and Security … Continue reading

Crowdedness of different philanthropic approaches

This section primarily organizes information presented above in order to summarize relative crowdedness of different areas of work on nuclear weapons policy.

The largest potential gaps in this space appear to be work on nuclear weapons policy outside of the U.S. and U.S.-based advocacy, with the former gap being larger but harder for a U.S.-based philanthropist to fill.

As mentioned above, very little foundation funding supports nuclear policy work abroad, which means that other countries have much more limited capacity for developing and advocating for policy related to nuclear weapons.[87]“The US has a far broader base of expertise on nuclear issues than most other countries do. It could be effective to contribute to the development of policy schools and think tanks internationally that would address nuclear issues, especially in the major countries that have nuclear weapons. The … Continue reading However, foundations have funded some work in this area:

- The MacArthur Foundation’s Asia Security Initiative supported increased communication and dialogue between policy analysts working on security issues relevant to Asia, including supporting researchers in Asia. This program has since ended.[88]“Asia Security Initiative Policy Research MacArthur ended the Asia Security Initiative in December, 2014. The Foundation is proud of the increased communication and dialogue its Asia Security Initiative has sparked between policy experts, and encouraged to see the work of its grantees being used … Continue reading

- The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has a satellite center in Moscow, and it has received funding from the Carnegie Corporation.[89]“Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, DC For the Carnegie Moscow center in support of the endowment’s global vision. 36 Months, $1,500,000. The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (the Endowment) is a global think tank with a mission to contribute to global security, … Continue reading

A majority of funding supports policy research and advanced education, especially from the large foundations in this space.[90]“Foundations supported a variety of strategies, but Policy Analysis and Research received nearly half of all funds.

About 47 percent of the funds — or over $120 million — recorded in the database [on peace and security funding] supported work that was intended for Policy Analysis and … Continue reading The Ploughshares Fund is the largest foundation focused primarily on advocacy, and is spending about $8M per year. Multiple people suggested to us that work on advocacy and communications were relatively neglected in nuclear weapons policy.[91]“Because governments control nuclear weapons, most philanthropic work tries to inform or influence government actions and policy regarding nuclear weapons. A big portion of philanthropic money goes into technical and policy research on nuclear issues. Communications gets fairly limited funding … Continue reading

We have a more limited sense of which areas are most crowded in terms of regional focus (e.g. Iran, Russia, South Asia, North Korea, United States) or objective pursued (e.g. preventing new states from getting nuclear weapons, decreasing the number of nuclear weapons held by countries that already have them, or securing nuclear materials to prevent terrorists from gaining access to them). However, our impression is that work related to potential conflict in South Asia—where the greatest threat is perceived[92]“Dr. Perkovich believes that the highest risk of nuclear war stems from conflict in South Asia. If there were another terrorist attack on a major Indian city that could plausibly be linked to Pakistan, there is a significant chance that India would respond with a conventional military attack on … Continue reading—is relatively crowded. Nuclear issues in South Asia receive substantial attention in the form of programs at universities and think tanks[93]“Many universities and think tanks have well-known programs related to South Asia. These programs in part aim to promote dialogue between groups and elites within both countries. The popularity of South Asia policy studies may be related to how potentially dangerous the region is from a nuclear … Continue reading as well as track II diplomacy, and some funders see little room for additional philanthropy on the topic.[94]“The use of nuclear weapons by India or Pakistan is seen by many in the sector at the most tangible area of short-term concern. An exchange of nuclear weapons between the two countries or an unauthorized or accidental use of weapons in the region would be catastrophic. However, there are limited … Continue reading We also note that in early 2015, the U.S. and Iran reached an agreement on a framework for monitoring Iran’s nuclear program, though we have a limited understanding of how this might affect philanthropic approaches related to non-proliferation in Iran.[95]“International negotiators assembled in Switzerland have announced the broad terms of the Iranian nuclear deal. Here they are, based on what we know, translated into plain English.

An important note: the deal is not yet finalized, and it is not particularly detailed. Thursday’s announcement is … Continue reading

Our impression is that the security of nuclear materials also receives significant attention. It is the primary focus of the Nuclear Threat Initiative,[96]“NTI’s chief focus is securing nuclear materials from falling into terrorist hands. It is very costly to manufacture nuclear materials such as plutonium and highly enriched uranium. These costs exceed what terrorists can afford. Therefore, preventing terrorists from acquiring nuclear materials … Continue reading and a priority for national governments.[97]“Dr. Perkovich believes that the risk of a nuclear attack by terrorists is generally exaggerated, though he remains unsure of this view because there are people he trusts who tell him he is wrong about this.[…] Governments are very much on top of this risk and it is unlikely that there is any … Continue reading

Questions for further investigation

We have not deeply explored this field, and many important questions remain unanswered by our investigation.

Amongst other topics, our further research on this cause might address:

- What are the options for a funder seeking to support work on nuclear weapons policy abroad, particularly in Russia or South Asia? What comparable work has been done in the past, and what is its track record?

- What other advocacy-based approaches could be pursued within nuclear weapons policy?

- What other strategies are there for reducing U.S./Russia nuclear inventories? Have we missed any particularly promising strategies that are not being pursued as aggressively as they could be? How would the potential severity of a nuclear winter decline as nuclear inventories shrink?

- What are the areas where policy research might lead to improved policy? What does such work typically involve? How has policy research in this field resulted in policy change in the past? Are any areas particularly neglected?

- To what extent could work normally classified under “international peace and security” but not “nuclear weapons policy” or “nuclear security” contribute to reducing the risk of a nuclear war?

- How likely is the detonation of a nuclear weapon or a broader nuclear escalation? Which sources or conflicts contribute the most to these risks?

Our process

We initially decided to investigate the cause of nuclear safety because:

- The potential devastation from the use of nuclear weapons is so great that an investment in nuclear safety could conceptually have high returns.

- Unlike some other global catastrophic risks, there is an established philanthropic community working to address nuclear safety issues.

We spoke with 12 individuals with knowledge of the field, including:

- Joe Cirincione, President, Ploughshares Fund

- Robert Einhorn, Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution

- Megan Garcia, Program Officer for the Hewlett Foundation’s Nuclear Security Initiative

- Erika Gregory, Founding Director, N Square: The Crossroads for Nuclear Security Innovation

- Bruce Lowry, Director of Policy and Communications, Skoll Global Threats Fund

- George Perkovich, Director of the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- Carl Robichaud, Program Officer, International Peace and Security, Carnegie Corporation

- Joan Rohlfing, President and COO, Nuclear Threat Initiative

- Gary Samore, Executive Director for Research, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School

- Philip Yun, Executive Director and COO, Ploughshares Fund

In addition to these conversations, we also reviewed documents that were shared with us and had some additional informal conversations.

Previous version of this page here.

Sources

| DOCUMENT | SOURCE |

|---|---|

| Carnegie Corporation Annual Report, 2013 | Source |

| Carnegie Corporation Nuclear Security Program Website | Source (archive) |

| Department of Homeland Security, Budget-in-Brief: FY 2015 | Source (archive) |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Bruce Lowry, November 5, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Carl Robichaud, October 14, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Erika Gregory, September 22, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Gary Samore, September 8, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with George Perkovich, June 6, 2013 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Joan Rohlfing, December 8, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Joe Cirincione, November 15, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Philip Yun, October 16, 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell’s non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Robert Einhorn, November 10, 2014 | Source |

| Hewlett Foundation Grants Database, 2015 | Source (archive) |

| Hewlett Foundation Nuclear Security Initiative Logic Model | Source |

| Hewlett Foundation Nuclear Security Initiative Webpage | Source (archive) |

| IAEA Regular Budget for 2014 | Source (archive) |

| Kristensen and Norris 2013 | Source (archive) |

| Kristensen and Norris 2014 | Source (archive) |

| MacArthur Foundation’s description of its nuclear security program, March 2014 | Source (archive) |

| MacArthur Foundation International Peace & Security Grant Guidelines, December 2014 | Source (archive) |

| National Nuclear Security Administration, About us | Source (archive) |

| National Nuclear Security Administration, Budget | Source (archive) |

| NTI 2012 Annual Report | Source (archive) |

| Nunn-Lugar Report for GiveWell’s History of Philanthropy Project by Benjamin Soskis, July 2013 (DOCX) | Source |

| Office of Technology Assessment 1979 | Source (archive) |

| Ploughshares Fund blog post | Source (archive) |

| Redstone Strategy Group 2012 | Source |

| Robock and Toon 2009 | Source (archive) |

| Robock et al. 2007 | Source (archive) |

| Shulman 2012 | Source (archive) |

| Stanton Foundation International and Nuclear Security Webpage | Source (archive) |

| Toon et al. 2007 | Source (archive) |

| Vox, Meet the political scientist who thinks the spread of nuclear weapons prevents war | Source (archive) |

| Vox, The Iran nuclear deal translated into plain English, April 2015 | Source (archive) |

| Wikimedia Commons, US and USSR nuclear stockpiles | Source |

| Xia et al. 2013 | Source (archive) |

Footnotes