Hepatitis Delta

Executive summary

Overall summary

This is a shallow investigation of hepatitis delta (“hepatitis D”). My goal was to estimate the disease burden attributable to the condition, learn about barriers to addressing the burden, and identify any promising opportunities that Coefficient Giving can fund. My investigation included a survey of the existing literature and a number of conversations with experts on hepatitis D and related matters.

While the burden of hepatitis D is highly uncertain, I used multiple approaches to estimate it, and I believe that it accounts for around 3.5 million DALYs each year. However, all variants of hepatitis are neglected, and hepatitis D is neglected even relative to the other variants; very little funding goes to address it specifically, likely because it is challenging to diagnose and difficult to treat.

There are several promising approaches that could allow for significant progress toward addressing hepatitis D, like developing better diagnostics or facilitating access to newer and more effective treatments. While I don’t think any of those approaches are strong enough for Coefficient to investigate further, other funders with different goals might find them interesting.

What is hepatitis D?

All of the hepatitis viruses (A, B, C, D, and E) cause liver inflammation. Hepatitis D, caused by hepatitis delta virus (HDV), is the most aggressive form of liver disease. It can only infect people who have already been infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), because it requires the presence of HBV to infect liver cells and replicate within them.

As a blood-borne virus, HDV can be transmitted through the use of contaminated needles, syringes, or other injection equipment, as well as through sexual contact. In rare cases, it can also be transmitted “vertically” — from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding.

Compared to HBV infection alone, having both HBV and HDV is associated with:

- A nearly fourfold risk of liver cirrhosis (scarring of the liver from repeated damage).

- A 28% increase in the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC — a type of cancer that affects liver cells).

- A reduced lifespan (since both conditions progress faster in people infected with HDV).

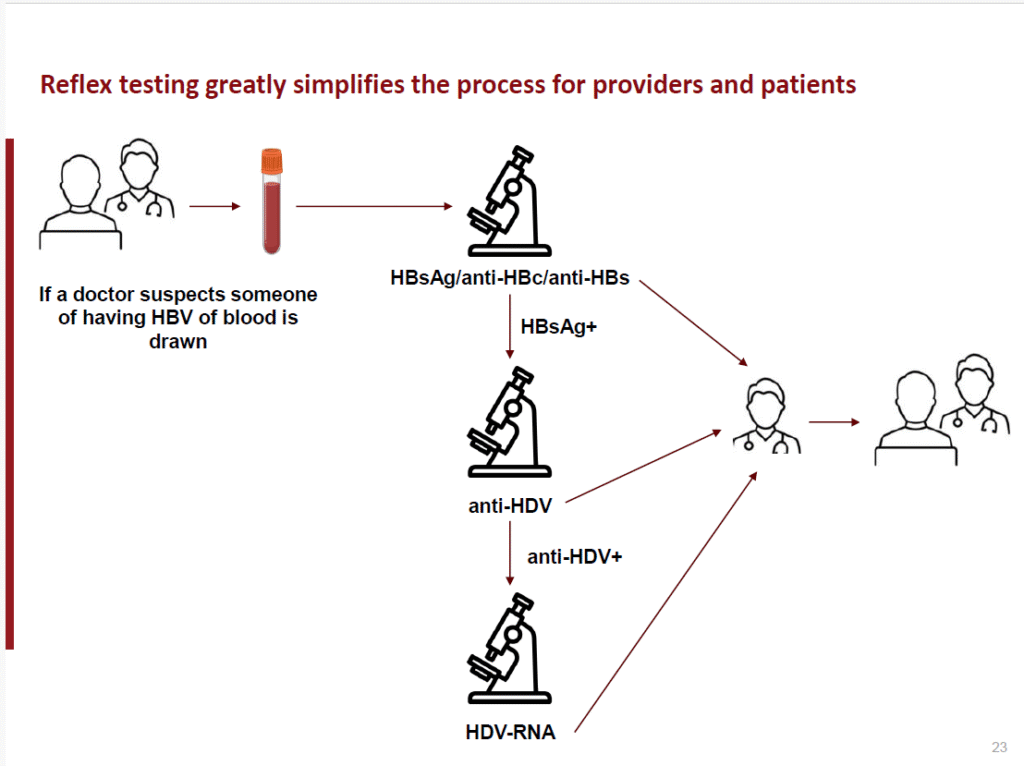

The WHO recommends HDV testing in all individuals who test positive for HBV. Following a positive HBV test, HDV can be diagnosed through a two-step process:

- Antibody screening that detects whether someone has been exposed to HDV (“anti-HDV testing”). Not all cases of HDV exposure progress to a chronic hepatitis D infection.

- RNA testing to confirm whether someone is actually infected, and to measure the viral load (as long as it falls within the range of levels the test can accurately measure).

The global prevalence of hepatitis D among those with HBV infection is estimated to be 4.5%. Globally, about 257 to 291 million people are chronically infected with HBV; of these, roughly 12 million are affected by HDV.

What is the problem?

Several factors are responsible for the continued prevalence of HDV:

Uncertain estimates of the burden: All experts we spoke with noted the paucity of epidemiological data on the burden of hepatitis D across various geographies. This lack of data typically leads health officials to underestimate the impact of HDV, which in turn leads to delayed or underfunded public health interventions.

Gaps in prevention efforts: While there is no cure for HBV, people can prevent hepatitis D by getting vaccinated against HBV or by taking other precautions (if already infected with HBV). Currently, the proportion of people covered by an HBV birth dose is lowest in the African region (18%) where HBV prevalence is highest. The complete vaccine series involves 2 to 3 additional doses following the birth dose.

Diagnostic challenges: Screening rates for HDV are low due to low awareness among health care workers, the lack of HDV-specific national guidelines, lack of point-of-care tests/laboratory-based testing requirements (which makes it harder to scale testing to everyone at risk), lack of commercial laboratory tests in many countries, the cost of current HDV tests, and the low reliability of some tests due to the high genetic variability of HDV — which leads to a high rate of false negatives and inaccurate viral load estimation, especially for HDV genotypes 5 to 8 (those primarily found in Africa).

Efficacy and cost of existing treatments: Existing treatments for HDV are not suited for a public health approach to treatment in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where most health care costs are paid out-of-pocket. Treatments include:

- Pegylated interferon-alpha (PegIFNα), administered as a weekly subcutaneous injection, which has been used as an off-label treatment for HDV for decades. Its use is limited by low efficacy (only 17% to 48% of those treated achieve negative HDV RNA levels after the recommended 48 weeks of treatment, with half of treated patients having a relapse), poor side effect profile, and contraindications. The cost of treatment is also high: roughly $1,250 for a 48-week treatment course.

- Bulevirtide, a drug developed by researchers at Heidelberg University, which has been approved for HDV treatment by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) but not yet by the FDA. It is administered as a daily subcutaneous injection; the treatment duration is yet to be defined.

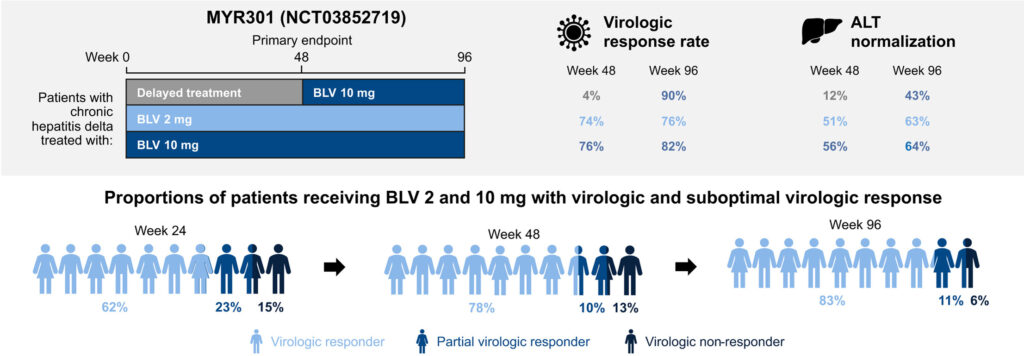

- Trial results show that people treated for a longer time have better responses. For the 2mg dose, virologic response rates at weeks 48 and 96 were 74% and 76%. For the 10mg dose, response rates at weeks 48 and 96 were 76% and 82%. These results are better than those typically observed with PegIFNα.

- However, bulevirtide is prohibitively expensive (e.g. €13,500 per month in Germany) and we are not aware of any current plans to make the drug more affordable or accessible in LMICs.

Importance

While the Global Burden of Disease study (“GBD”) publishes estimates for the DALY burden of HBV, it doesn’t do so for HDV. However, we can use the former to estimate the latter. Below, I explain several approaches I used to create my estimate:

| Estimation Method | Notes | Implied HDV DALY Burden | HDV Burden as % of HBV Burden |

| Using PAF (Population Attributable Fraction) estimates of HDV | From Stockdale et al. (2020), 18% of cirrhosis cases and 20% of HCC cases in HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen) positive individuals can be attributed to HDV. I apply this to the DALYs from liver cirrhosis and liver cancer due to hepatitis B. | 3.4M | 17% |

| Based on HDV risk multipliers | Miao et al. (2020) report a 3.8x higher risk of developing cirrhosis, and Alfaiate, Dulce, et al. (2020) report a 1.28x higher risk of developing HCC among coinfected patients compared to HBV monoinfection. | 2.34M | 11% |

| Scatter plot/regression | Correlation between HBV DALY rate (GBD estimates) and anti-HDV prevalence for selected countries, from Stockdale et al. (2020). | 4.3M | 21% |

WHO estimates that 1.1 million deaths were caused by hepatitis B in 2022. Coefficient estimates that premature death (for people over 5 years of age) accounts for an average of 32 DALYs. If we assume that HDV accounts for 16.3% of the health burden from HBV (the average of the numbers in the last column above), that would imply that HDV accounted for ~5.7 million DALYs in 2022.

Neglectedness

In my research and conversations with experts, I found that HDV is highly neglected, especially in terms of philanthropic funding (as distinct from government spending or private investment). One expert described HDV as relatively neglected even within the neglected field of hepatitis. HDV funding is largely integrated into broader hepatitis initiatives (which typically prioritize other forms that are easier to diagnose, prevent, and treat). Without dedicated funding, hepatitis D will likely continue to be overlooked — slowing down targeted research and policy attention.

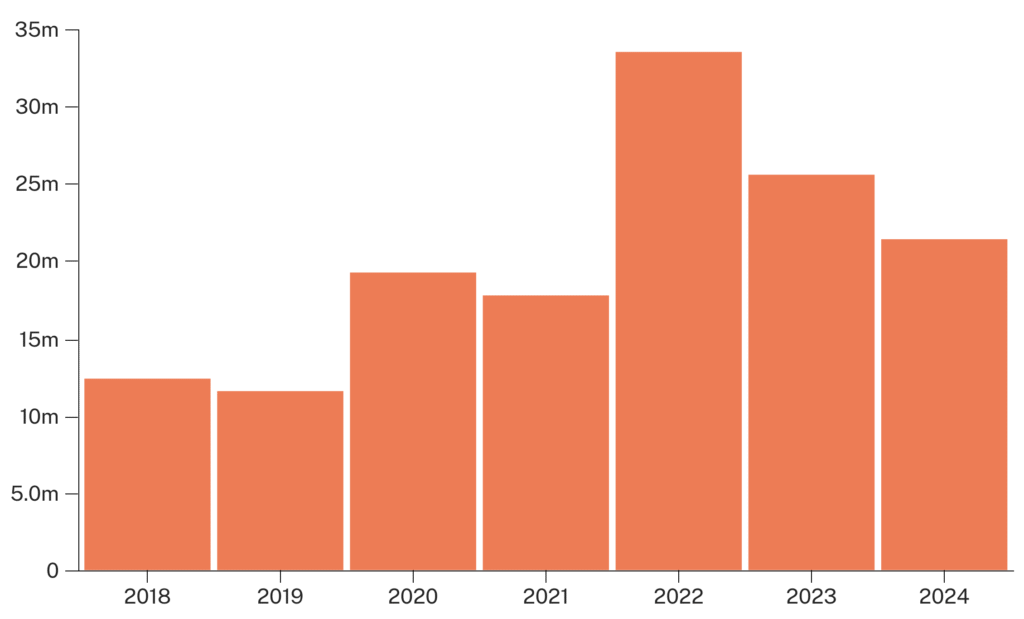

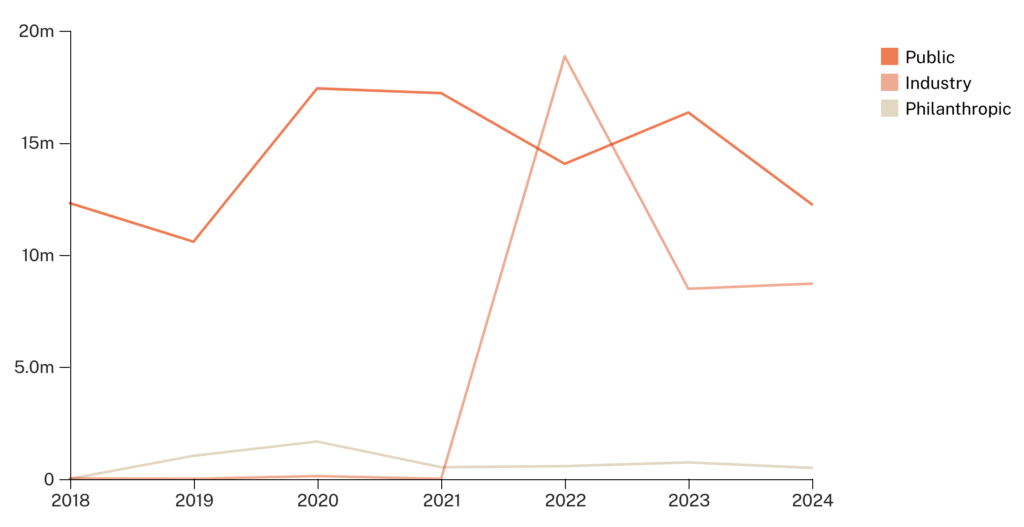

While G-FINDER does not publish funding data for R&D spending toward HDV, we can use HBV as a proxy. For each DALY of global burden from HBV, G-FINDER reports $1.20 in R&D spending. This is quite low compared to spending for tuberculosis ($17/DALY), HIV/AIDS ($32/DALY), and malaria ($13/DALY). Total funding for HBV R&D in 2023 was $25 million, comprising $16 million from public funds, $8.3 million from industry funds, and $0.3 million from philanthropic funding (specifically from Wellcome Trust).

Public health work to address the burden of HDV also seems to be highly neglected. I could not find any organization working specifically on HDV; most organizations focus on HBV and/or HCV. That said, some funding goes toward efforts to eliminate hepatitis generally. Organizations in that space include The Hepatitis Fund, the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination, the CDA Foundation, the Hepatitis B Foundation, the John C. Martin Foundation, and Wellcome Trust. Multilateral organizations include the D-SOLVE Consortium, Unitaid, and Gavi.

Tractability

Despite the challenges I’ve highlighted for HDV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, I think there are opportunities for cost-effective spending in this area. I ran BOTECs (back-of-the-envelope calculations) on several potential opportunities; below, I list a few that were sufficiently promising to merit further exploration. In most cases, ideas that weren’t listed seemed likely to be much less cost-effective than our bar for grantmaking requires and/or very difficult to estimate.

| Potential Opportunity | SROI |

| Research to collect better estimates of HDV prevalence (more) | 301x |

| Improved HDV diagnostics (rapid diagnostic tests for HDV screening) (more) | 789x |

| Improved HDV diagnostics, plus supporting access to a generic version of a particular (oral) HDV treatment (more) | 1,773x |

| Higher uptake of hepatitis B birth dose vaccination (more) | 1,833x |

All names of organizations have been anonymized. As of the publication of this research, we target a ~2000x “bar” for SROI (social return on investment).

While vertical transmission (mother-to-child) is rare for HDV, it is how most new HBV infections occur. Therefore, improved coverage of the hepatitis B vaccine in infancy and early childhood, beginning with the hepatitis B birth dose vaccine, will significantly reduce new HBV infections and consequently prevent new HDV infections. This, however, will not improve morbidity or mortality outcomes for those already chronically infected with HBV and HDV.

For this group, I am most excited about opportunities that could improve access to testing via the development and distribution of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and point-of-care tests. These tests would enable clinic-based and possibly community-based testing for HBV and HDV. However, I think this approach would be more impactful if we simultaneously supported efforts to make an improved treatment option available — one cheap enough to be accessible to patients in LMICs.

I am skeptical that this area is promising enough to merit further investigation from Coefficient; the highest impact levels I estimated are below our bar. However, governments and other funders with different goals might want to pay more attention to HDV; they could easily look at the same data I did and reach a different conclusion.

Background

The term “hepatitis” can refer to any inflammation of the liver. The most common form is viral hepatitis, which is caused by five distinct viruses (A, B, C, D, and E). Other forms have non-viral causes, from metabolic and autoimmune conditions to heavy alcohol consumption.

Of the hepatitis virus strains, A and E are mainly transmitted via the fecal-oral route and rarely progress to chronic infection; B, C, and D are blood-borne and can cause chronic infection. B, C, and D are the most common causes of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and they cause most of the deaths related to hepatitis.

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV), discovered in 1977, is the cause of hepatitis D. The relationship between hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HDV is that HDV depends on HBV to replicate within cells. This means that HDV infection can only occur in individuals who are already infected with HBV or acquire both HBV and HDV simultaneously.

Individuals with concurrent HBV and HDV infection are at risk of the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis. Compared to HBV infection alone, the accelerated liver damage from concurrent infection with both viruses causes a faster progression to liver fibrosis, liver cirrhosis, and HCC. Miao et al. (2020) quantified the risk of liver cirrhosis progression as 3.8x higher in HBV/HDV coinfection compared to HBV mono-infection.

There are two possible patterns of HDV transmission:

- Coinfection: This describes when an individual is infected with both HBV and HDV at the same time. This can cause mild acute hepatitis or severe or fulminant hepatitis, but in ~95% of cases, leads to clearance of both viruses (that is, a resolution of the infection) within 6 months, with only ~5% leading to chronic infection.

- Superinfection: This happens when an individual is infected with HDV after an earlier infection with HBV. In most cases (>80%), this persists and progresses to a chronic HDV infection, resulting in liver cirrhosis and increased risk of HCC compared to HBV mono-infection.

How HDV is diagnosed

Following a positive HBsAg test (indicating active HBV infection), HDV can be diagnosed through a two-step process:

- Antibody screening that detects whether someone has been exposed to HDV (“anti-HDV testing”). Not all cases of exposure progress to a chronic hepatitis D infection.

- If the anti-HDV test is positive (indicating exposure), proceed to RNA testing to confirm whether someone is actually infected, and to assess viral replication.

In 2024, the WHO began to recommend “reflex testing” for HDV — that is, testing anyone who has tested positive for HBsAg.

Figure 1: Reflex testing for HDV diagnosis following positive HBsAg result (source: Hep B Foundation).

What is the problem?

Multiple factors contribute to the burden of HBV/HDV coinfection, ranging from the difficulty of even estimating the burden to gaps in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment.

Uncertain estimates of the burden of HDV

Several experts I interviewed acknowledged the lack of proper epidemiological estimates of the prevalence or impact of HDV infection.

Good data is hard to find for several reasons:

- The other four variants are easier to test for; there are affordable, standardized tests for them (but not for HDV — see “diagnostic challenges”).

- Many studies that include anti-HDV testing don’t proceed to RNA testing (making it impossible to confirm which subjects were actually infected).

- Few national serosurveys have been conducted to measure HDV prevalence; existing estimates are based on testing among members of high-risk groups, which could make them overestimates for the general population. However, my best guess is that prevalence is still underestimated in most contexts: the experts I spoke with believe this, and I think the lack of available testing typically leads governments to assume infection isn’t a widespread problem (despite what the available data implies).

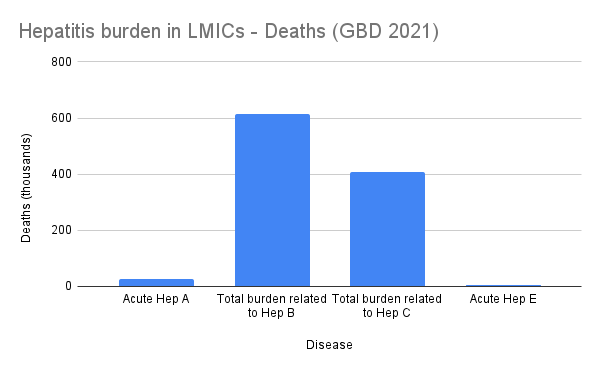

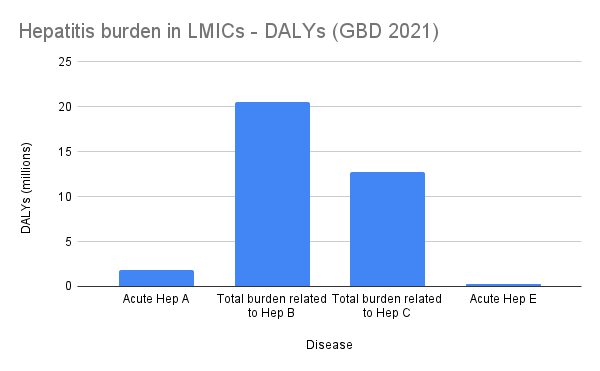

The image below shows the GBD 2021 death and DALY burden estimates for hepatitis A, B, C, and E. GBD does not publish death or DALY estimates for HDV, but its impact is likely reflected under HBV.

Figure 2: Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 estimates for the number of deaths associated with hepatitis A, B, C, and E.

Figure 3: Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 estimates for the number of DALYs associated with hepatitis A, B, C, and E.

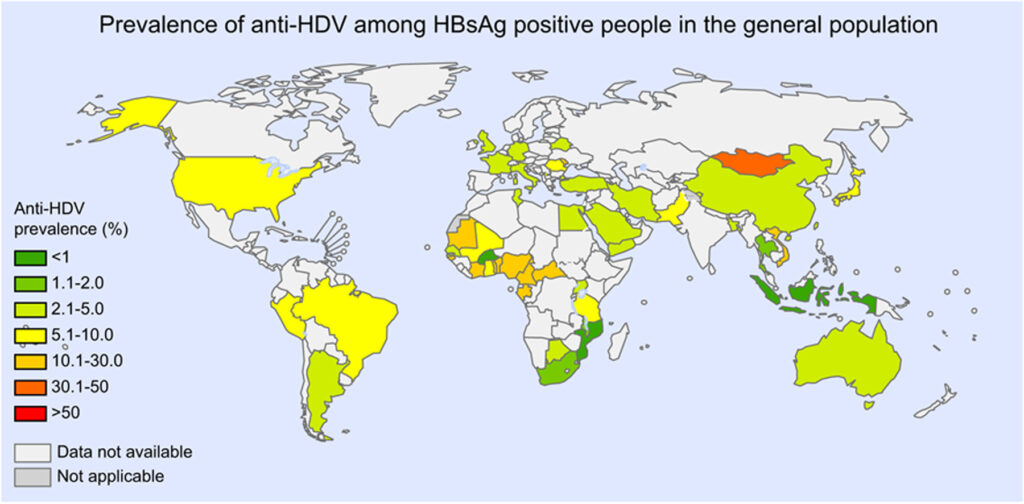

The most commonly referenced estimates for the prevalence of HDV come from a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in collaboration with the WHO (Stockdale et al. 2020).

Key findings from the research:

- ~257 to 291 million people have chronic HBV infection.

- The estimated global anti-HDV prevalence is 0.16% in the general population, 4.5% among people who test positive for HBsAg, and 16.4% in those attending hepatology clinics. In other words, ~12 million people worldwide are affected by HDV.

- The burden of HDV is uncertain and varies across regions (see map below).

- Certain geographies (Mongolia, the Republic of Moldova, and countries in Western and Middle Africa) and populations (injecting drug users, hemodialysis recipients, men who have sex with men, commercial sex workers, and those with HCV or HIV), were found to have a higher prevalence of hepatitis D than other HBsAg-positive individuals.

- Among individuals who are HBsAg-positive, 18% of cirrhosis cases and 20% of HCC cases could be attributed to hepatitis D.

According to the WHO, the WHO Western Pacific and African Regions have the highest HBV burden, with 97 million and 65 million people chronically infected.

Figure 4: Global prevalence of hepatitis D (source: Stockdale et al. (2020))

Obstacles to prevention

HDV can be prevented in multiple ways:

- While there is no HDV-specific vaccine, people can be vaccinated against HBV, either as infants beginning at birth or adults. Infant vaccination is more effective.

- Health care and harm reduction services can adopt safer practices around blood transfusions, injections, and sexual health to reduce the risk that patients with HBV also contract HDV — similar to efforts aimed at preventing blood-borne viral infections and sexual transmission.

However, there are several obstacles to widespread prevention efforts:

- In 2022, only 45% of infants worldwide received the HBV vaccine within 24 hours of birth, including only 18% in the African region (which has the highest prevalence of hepatitis B).

- At present, there is no way to completely clear HBV infection from the body. If there were, clearing out HBV would end HBV HBsAg production and lead to the eventual clearance of HDV. Current treatments for HBV, like tenofovir and entecavir, are focused on suppressing viral replication and reducing viral loads to very low levels, which reduces liver damage and lowers the risk of complications. However, this level of reduction still isn’t enough to prevent HDV replication.

Few people are actually tested for HDV. This contributes to the aforementioned challenge: it’s hard to estimate the burden of HDV without widespread testing.

Barriers to HDV testing include:

- Awareness: Some health care workers (HCWs) aren’t aware they should test for HDV in patients with HBV infection. Others may not prioritize this testing over other work because of limited resources, limited therapeutic options, the lack of treatment policies, or underestimation of the prevalence of HDV.

- Infrastructure and cost for conducting HDV testing: Compared to HDV testing, HBV testing is relatively simple due to the availability of an HBsAg rapid diagnostic test (RDT) that is cheap to administer, requires minimal infrastructure, delivers results in minutes, and can be used in a community setting. According to the WHO, the HBsAg RDT is currently priced at $1 per test (public sector procurement price) and the cost for HBV DNA testing in selected countries ranged between $9 and $62 in 2022.

- Unlike for HBV, there are currently no commercially available RDTs for HDV, which means that tests can only be done in laboratories. This raises the cost of HDV screening, delays diagnosis, and reduces access to treatment in LMICs.

- Uptake of HDV testing will be facilitated by the availability of an RDT, preferably a dual or other combination RDT that also allows for HBV screening (and isn’t more expensive than other HBV tests). This is especially relevant in LMICs, where people typically pay out of pocket for viral hepatitis diagnostics.

- Reliability of HDV RNA assays: Even when HDV testing is available, test quality varies significantly. There are eight HDV genotypes (and several subgenotypes) found in different parts of the world. This heterogeneity and the lack of standardization across testing laboratories causes a variation in the HDV detection and quantification performance of both commercial and research-based HDV RNA assays. For example, some assays — particularly those that have not been validated across diverse genotypes — underestimate (and in some cases fail to detect) viral load levels in patients whose HDV has an African genotype (HDV-5 to -8). A recent review (Wedemeyer et al. (2025)) recommends that HDV RNA assays:

- Be calibrated to the WHO HDV RNA international standard.

- Be able to detect genotypes HDV-1 to -8.

- Use an internal control for process monitoring.

- Low screening rates for HBV: Despite the availability of a low-cost RDT for HBV screening, the WHO reported that at the end of 2022, only 13% of people living with chronic HBV infection had been diagnosed. HDV screening follows an initial screening for HBV. Consequently, low uptake of screening for HBV negatively impacts HDV diagnosis.

- Testing guidelines: While the WHO now recommends routine anti-HDV screening for patients with HBV infection (“reflex testing”), not all national guidelines match this recommendation.

In summary, the following strategies should serve to increase HDV diagnosis rates:

- Creating better diagnostics for HDV and making them more widely available and affordable.

- Scaling up HBV testing and more reliably testing for HDV in people found to be HBV-positive.

Efficacy and affordability of available treatment options

Treatment for HDV aims to prevent the progression of liver damage, cirrhosis, liver cancer, and death from liver disease. As these outcomes require long-term follow-up, they are hard to assess in clinical trials. Alternative ways to monitor response to treatment include:

- Checking for HBsAg clearance (which indicates suppression of HBV).

- Checking whether HDV RNA has been suppressed (reduced to below measurable levels).

- Checking for an HDV RNA decline of more than 2 log IU/mL from baseline (which indicates that a treatment is working even though suppression hasn’t yet been achieved).

Unfortunately, current methods for treating HBV, even if they sharply reduce HBsAg levels, do not affect HDV viral load or outcomes. HBV integrates its own DNA into human cellular DNA, leading that cellular DNA to produce HBsAg. Fully stopping HBsAg production is impossible with current methods, and even a small amount of HBsAg enables HDV to keep reproducing. However, if a method were found to completely clear HBsAg, HDV would also eventually be cleared.

Current treatment options

For decades, pegylated interferon-alfa (PegIFNα) has been used in the treatment of HDV despite the absence of any regulatory approval for this usage (its use is off-label). It is administered as a subcutaneous injection once weekly, and treatment typically lasts for 48 weeks. However, its use has been limited by contraindications, poor side effect profile, and poor virologic response rates.

The response rates (defined by HDV RNA negativity) for treatment with PegIFNα range from 17% to 48%, and with long-term follow-up of 5 years, 50% of these cases had a relapse.

Despite these limitations, PegIFNα is still recommended by the WHO for HDV infection, as treatment reduces the risk of disease progression.

In 2020, bulevirtide, developed by researchers at Heidelberg University, received conditional approval and subsequently full approval in 2023 from the European Medicines Agency for HDV treatment. It is currently the only approved treatment for HDV, is administered as a daily subcutaneous injection, and has demonstrated improved reduction in HDV viral load. Phase 3 results of an RCT (MYR301) which randomized 150 patients 1:1:1 to 2mg bulevirtide for 144 weeks, 10mg bulevirtide for 144 weeks, and delayed treatment for 48 weeks followed by 10mg daily for 96 weeks showed improved virologic and biochemical responses with longer duration of treatment.

Figure 5: Virologic and biochemical responses from the MYR301 Phase 3 trial of bulevirtide in patients with chronic HDV (source: Wedemeyer et al. (2025))

Combination treatment comprising bulevirtide and PegIFNα is associated with better responses to treatment. However, viral rebound occurs with discontinuation of treatment; thus, a recommended duration of treatment has not been established.

In 2022, the U.S. FDA rejected an application for approval of bulevirtide to treat HDV, due to issues with “manufacturing and delivery.” So for now, Gilead isn’t able to market the drug in the U.S. Gilead is yet to refile an application with the FDA.

Treatment costs

In LMICs, where most health care costs are paid out of pocket, medication prices are a major determinant of access to treatment.

Pegasys (PegIFNα-2a), manufactured by Roche, is sold as a prefilled injection of 180mcg/mL (which constitutes a weekly dose). I found that private pharmacies in Nigeria sell Pegasys at a price of 40,000 Nigerian Naira (~$26) per dose, which translates to ~$1,250 for a 48-week treatment course (slightly below Nigeria’s per capita GDP).

Interferon-based treatments were used for HCV treatment prior to the introduction of direct acting antiretroviral (DAA) drugs for HCV in 2014. According to a CHAI market report, this reduced the cost of HCV treatment from over $3,000 for a course of interferon-based treatment to $60 for a 12-week complete treatment course of DAAs in 2019. Treatment for HBV is available at a global benchmark price of $2.40 per month (~$30 per patient, per year). Market shaping efforts by organizations such as CHAI and Medicines Patent Pool have improved access to hepatitis B and C treatment via pricing negotiations, transparency, and generic licensing.

There are other reports of efforts by governments to reduce the cost of interferon-based treatment for hepatitis. For example, in Egypt, local manufacture of a version of PegIFNα enabled negotiations with Roche and Merck to drive down the price to $2,000 for a treatment course in 2013.

Zöllner et al. (2022) report the cost of bulervirtide at €13,500 per month in Germany. Another report lists the price for bulevirtide treatment as £6,500. According to the Medicines Patent Pool, the primary patent for bulevirtide has been granted in key manufacturing countries such as India, China, Brazil, and South Africa, with an expected expiration in 2028. There is no information on plans for access to bulevirtide in LMICs, and Dr. Stephan Urban — in a webinar presentation hosted by the CGHE — mentioned that the lack of a defined treatment period also makes companies less likely to issue discounted/”compassionate use” prices, since it makes the cost of a discount harder to estimate.

While market shaping efforts have historically driven down prices, it is not clear what the route to improved access to affordable treatment in LMICs will be, or how quickly that can happen given the high current prices.

Complicating factors

Before HDV treatment can commence, patients are required to undergo further liver tests (e.g. transient elastography to check for kidney scarring/fibrosis) to assess the severity of the disease and ensure that treatment can be safely tolerated.

Additionally, both PegIFNα and bulevirtide are administered via weekly and daily injections respectively, and require cold chain storage. While they can be administered in outpatient settings, patients need to attend the clinic for the first couple of doses for training on self-administration, and regularly thereafter for monitoring.

The required testing and clinic attendance add further cost and complication to the treatment process, posing a considerable challenge in resource-limited settings.

Importance

In this section, I estimate the DALY burden of HDV using information from GBD, the Stockdale paper, and the WHO global hepatitis report.

Population attributable fraction (PAF) estimates of HDV

Since IHME/GBD does not publish data for HDV, I roughly estimate the burden using published data on HBV mortality and DALY burden. Globally and in LMICs, GBD’s estimate for the total DALY burden from hepatitis B is largely accounted for by chronic hepatitis B, including cirrhosis (~65%) and liver cancer (~25%). Less than 10% is due to acute hepatitis.

| Cause | DALYs | % of Total Burden |

| Acute hepatitis B | 1.9M | 9% |

| Liver cancer due to hepatitis B | 5.2M | 25% |

| Chronic hepatitis B including cirrhosis | 13.4M | 65% |

| Total burden related to hepatitis B | 20.5M |

Figure 6: Contributions to total DALY burden related to hepatitis B in LMICs

Population attributable fraction (PAF) estimates suggest that HDV accounts for 18% of cirrhosis cases and 20% of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cases among HBsAg-positive individuals.

Using these estimates, HDV is responsible for:

- 18% of the DALYs from chronic hepatitis B, including cirrhosis: that’s 2.4 million DALYs.

- 20% of the DALYs from liver cancer due to hepatitis B: that’s 1 million DALYs.

This sums up to 3.4 million DALYs annually in LMICs due to HDV, coming from liver cancer and cirrhosis (but excluding acute hepatitis, which makes this a lower-bound estimate).

According to the Stockdale paper, HDV is estimated to affect ~4.5% of individuals with chronic HBV infection, yet it accounts for 17% (3.4M/20.5M) of all HBV-related DALYs.

If HDV was responsible for only 4.5% of DALYs (i.e., in proportion to its prevalence), the expected DALY burden would be ~0.9 million DALYs (0.045 * 20.5). The fact that a lower bound estimate of HDV DALYs is 3.4M/20.5M = ~17% of the total burden despite the fact that hepatitis D is only responsible for 4.5% of the cases suggests that the DALY burden for a case of HDV is ~4.3x higher than for a case of HBV.

HDV risk multipliers

Multiple studies compare health outcomes from patients with HBV/HDV coinfection, relative to those with HBV monoinfection. In a meta-analysis, Miao et al. (2020) report a 3.8x higher risk of developing cirrhosis; Alfaiate et al. (2020) report a 1.28x higher risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Based on these numbers and the table above:

- Risk of liver cirrhosis (65% of total hepatitis B DALY burden) is 3.8x higher with HDV infection.

- This implies that hepatitis D is (3.8*0.045)/((3.8*0.045) + (1*0.955)) = ~0.152, or ~15.2% of the liver cirrhosis burden = ~2.04 million DALYs.

- Risk of HCC (25% of total hepatitis B DALY burden) is 1.28x higher with HDV infection

- This implies that hepatitis D is (1.28*0.045)/((1.28*0.045) + (1*0.955)) = ~0.57, or ~5.7% of the liver cancer burden = ~0.3 million DALYs.

- Therefore, the HDV DALY burden is ~2.04 million + ~0.3 million = ~2.34 million DALYs.

Correlation between HBV DALY rate and anti-HDV prevalence for selected countries

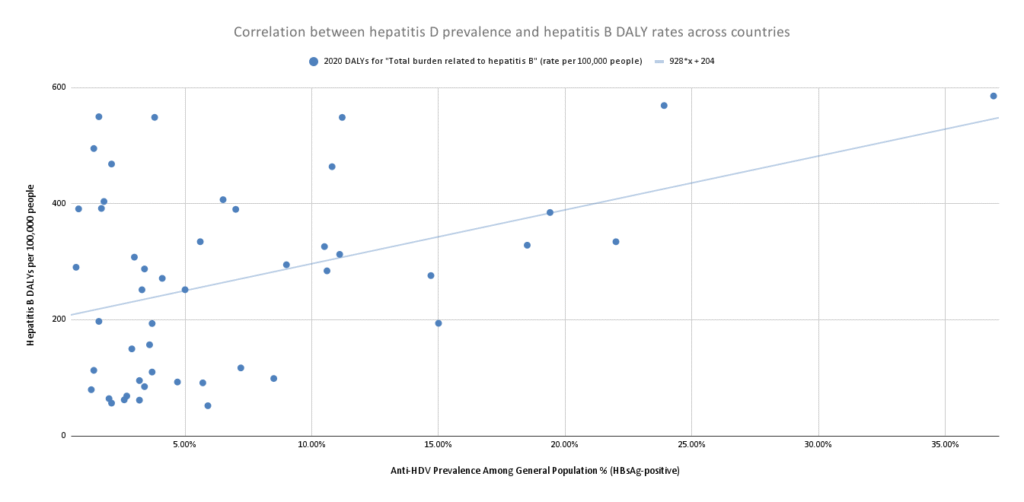

Using data from GBD, I created a scatter plot to check for correlation in selected countries between HBV DALY rates (for 2020) and published estimates of anti-HDV prevalence from Stockdale et al. (2020).

Figure 7: Scatter plot showing relationship between hepatitis D prevalence and total burden related to hepatitis B across countries

This chart reflects the regression equation 928x + 204, where:

- x represents the % of HBV-infected individuals coinfected with HDV (i.e. HDV prevalence among HBsAg-positive individuals).

- For every additional 1% of the population with hepatitis D (given that they have hepatitis B), the DALY burden increases by 9.28.

- How to think about these figures:

- If hepatitis D didn’t exist (x = 0), the DALY burden would be 204 DALYs per 100,000.

- If every person with hepatitis B also had hepatitis D (x = 1), the DALY burden would be 204+928 = 1,132 DALYs per 100,000.

- That suggests that a case of hepatitis D (coinfected with hepatitis B) is 1,132/204 = ~5.6x the DALY burden of hepatitis B.

- This implies that hepatitis D is (5.6*0.045)/((5.6*0.045) + (1*0.955)) = ~0.21, or ~21% of the hepatitis B burden = ~4.3 million DALYs.

Note that this is a very rough estimate: confounders could include access to better health care and antiviral treatment, higher HBV vaccination coverage rates, higher GDP, or higher literacy rates. There is also the possibility of “reverse causation” — a higher rate of hepatitis B cases could cause a higher rate of hepatitis D among the hepatitis B population (e.g. if hepatitis D is more likely to develop in areas with a higher concentration of hepatitis B, perhaps because that high concentration could imply a higher rate of risky behavior like needle sharing). One could investigate this further by running a series of country regressions with more controls.

Overall, these three estimates imply that hepatitis D accounts for between 11% and 21% of the total burden from hepatitis D.

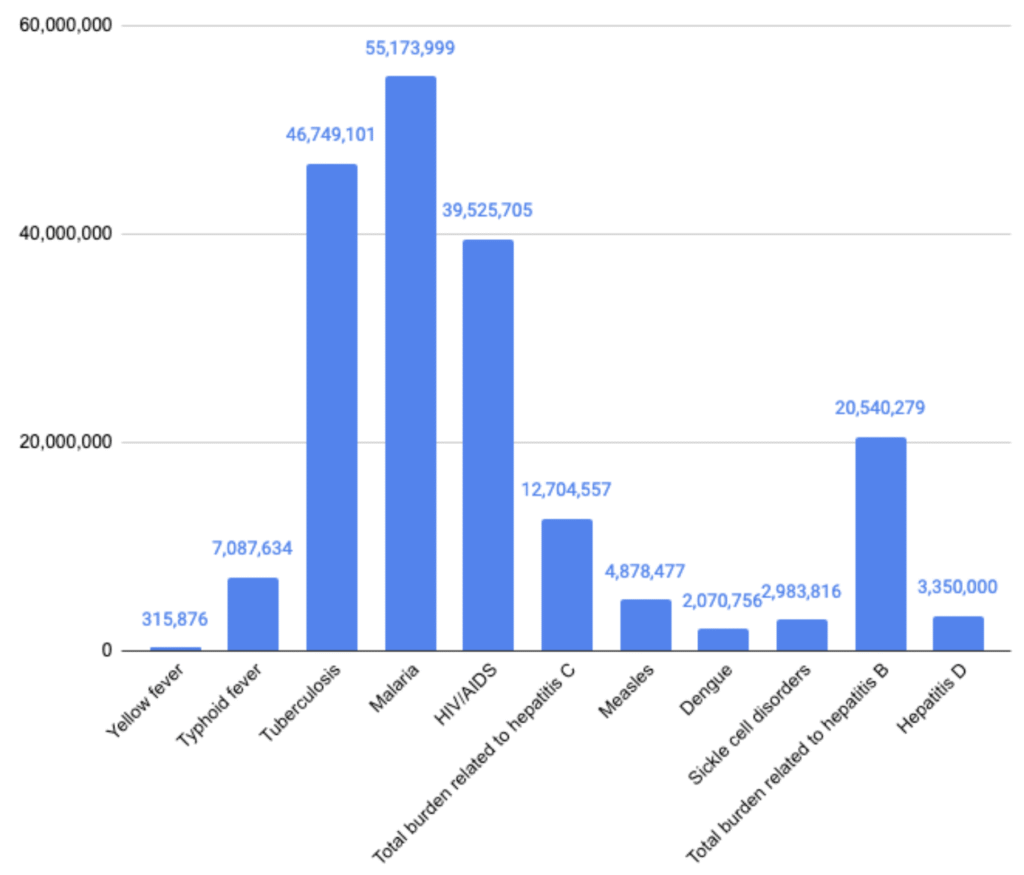

The chart below shows how hepatitis D compares to other disease areas, taking the average of the three estimates above (3.4M, 2.34M, and 4.3M) to get a DALY burden of 3.35 million:

Figure 7: LMIC DALYs per disease area (GBD 2021 estimates)

WHO estimates on mortality from viral hepatitis

Additional data from the WHO’s global hepatitis report (2024):

- An estimated 254 million people are living with hepatitis B globally.

- This implies that ~11.4 million people are living with HDV: ~4.5% of 254 million.

- Data from 187 countries show an estimated 1.3 million deaths from viral hepatitis in 2022 — an increase from 1.1 million in 2019.

- 83% of these 1.3 million deaths from viral hepatitis in 2022 (~1.1 million deaths) were caused by hepatitis B.

- When CG creates BOTECs, we estimate that premature death (for people over 5 years of age) accounts for an average of 32 DALYs.

- ~1.1 million * 32 = ~35.2 million DALYs.

- If we assume that HDV burden accounts for 16.3% of HBV burden (the average from the three estimates above), it would account for ~5.7 million DALYs.

Ways these estimates could be wrong

Accurately estimating HDV prevalence is challenging due to data limitations, biases, the low reliability of testing methods, and reporting gaps. Stockdale et al. (2020) included data from settings at high risk of bias and did not address trends in anti-HDV prevalence.

Some other studies suggest that HDV prevalence may be higher:

- A systematic review and meta-analysis by Chen et al. (2019) found an HDV prevalence of 14.57% among HBsAg-positive individuals.

- Miao et al. (2020) reported an HDV prevalence of 13.02% among HBsAg-positive individuals.

A more recent study by the Polaris Observatory Collaborators provided an adjusted estimate of the prevalence of HDV in 25 countries and territories. They found lower estimates than previously reported for 18 countries.

Better assessments of anti-HDV prevalence will require large sample sizes to identify people with HBV, which is challenging in areas with low HBV prevalence and/or low HBV testing uptake. Several experts noted that while the data on HDV epidemiology is scarce, they think the prevalence of HDV is underestimated due to low testing rates for HBV. Regional variations in HBV vaccination uptake can also affect HDV prevalence. 63% of new HBV infections occur in Africa, which has the lowest vaccination rates.

Neglectedness

According to the WHO, funding for viral hepatitis remains limited: it accounts for nearly eight times as many prevalent infections as HIV, and yet receives less than 10% as much funding. Hepatitis D seems fairly neglected, though I wasn’t able to find estimates of annual spending specific to that variant. It is plausible that funding for HDV programs is often integrated into broader viral hepatitis initiatives, especially those that target HBV. My low-confidence estimate, based on conversations with experts and desk research, is that roughly 5% (2-10%) of total funding for hepatitis B initiatives goes toward HDV. Niklas Luhmann of the WHO described hepatitis D as neglected within the neglected field of viral hepatitis.

Global R&D funding

Funding for HDV-specific public health interventions, such as market shaping or implementation science, is extremely limited in LMICs.

While G-FINDER does not publish funding data for R&D spending toward HDV, we can use HBV as a proxy. For each DALY of global burden from HBV, G-FINDER reports $1.20 in R&D spending. This is quite low compared to spending for tuberculosis ($17/DALY), HIV/AIDS ($32/DALY), and malaria ($13/DALY). Total funding for HBV R&D in 2023 was $25 million, comprising $16 million from public funds, $8.3 million from industry funds, and $0.3 million from philanthropic funding (specifically from Wellcome Trust).

Figure 9: Trends in HBV R&D funding from 2018 to 2023 (source: G-FINDER)

Compared to disease areas like tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and malaria, R&D funding for hepatitis B and C is neglected — as seen in the Total $/DALY column in the table below.

| Disease Area | 2021 DALYs | 2023 Total R&D funding | Total $/DALY | 2023 Philanthropic funding | % Philanthropic funding | Philanthropic $/DALY |

| Hepatitis (B+C combined) | 36,653,299 | $46,000,000 | $1.3 | $1,700,000 | 4% | $0.05 |

| Hepatitis B | 21,465,451 | $25,000,000 | $1.2 | $700,000 | 3% | $0.03 |

| Hepatitis C | 15,187,848 | $21,000,000 | $1.4 | $1,000,000 | 5% | $0.07 |

| Tuberculosis | 46,977,463 | $806,000,000 | $17 | $247,000,000 | 31% | $5.26 |

| HIV/AIDS | 40,266,792 | $1,269,000,000 | $32 | $134,000,000 | 11% | $3.33 |

| Malaria | 55,174,061 | $690,000,000 | $13 | $201,000,000 | 29% | $3.64 |

Figure 10: R&D funding by disease area vs. DALY burden (source: G-FINDER)

Philanthropic funding

Below, I list organizations that fund work on HBV and/or HCV (mostly for implementation science, public health awareness, and modeling), which could serve to indirectly address the burden of HDV.

The Hepatitis Fund (THF) is a grantmaking organization founded in 2017 as a partnership between the ZeShan Foundation, WHO, and the U.S. CDC. It describes itself as the first and only grantmaking organization dedicated to ending viral hepatitis. With grant amounts ranging from ~$33K to ~$950K, the organization is focused on the elimination of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in Asia-Pacific and Africa, though a few grants address viral hepatitis generally. THF and CHAI hosted the Global Hepatitis Resource Mobilisation Conference in May 2023, which resulted in commitments from countries, pharmaceutical companies, and several foundations.

The Task Force for Global Health is a U.S.-based nonprofit organization that supports large-scale public health programs globally, and includes viral hepatitis as one of its focus areas. The Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination (CGHE) was established by the task force in 2019, and works on viral hepatitis prevention, testing, and treatment via provision of technical assistance, knowledge generation and sharing, and advocacy.

The Center for Disease Analysis (CDA) Foundation is a nonprofit organization focused on eliminating hepatitis B and C globally by 2030. It founded the Polaris Observatory, which provides modeling data on the impact of HBV and HCV disease progression and supports governments to use that data to inform elimination strategies. The foundation disbursed $5.9 million between 2017 and 2024, comprising $2 million in international grants and $3.9 million in U.S. grants (all for cross-cutting activities, none specific to HDV).

The Hepatitis B Foundation, though focused on finding a cure for HBV and improving the lives of those affected by the disease, launched a program called HepDConnect to increase awareness and provide information on HDV. The foundation also funds research through the Baruch S. Blumberg Institute.

The John C. Martin Foundation funds some work on viral hepatitis, including a grant to understand the epidemiology of HDV across China (amount not specified).

I reviewed the grants database of the Wellcome trust and found no grants specific to HDV. Two HBV grants were awarded in 2021, totaling ~£430K.

Bilateral and multilateral agencies

Unitaid’s Eliminating Vertical Transmission portfolio (~$25 million) covers HIV, HBV, syphilis, and Chagas disease under a new project with PATH and partners: SAFEStart+.

Gavi, as part of its vaccine investment strategy, provides funding to some countries to introduce the hepatitis B birth dose vaccination.

The Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and Malaria (GFATM) policies have been expanded to include support to reduce the impact of HBV and HCV within HIV programs.

Governments

Mongolia has one of the highest HDV burdens globally, with a prevalence of ~40% amongst those with HBV. In 2024, the government of Mongolia stated that it would cover the cost of HDV treatment, though the funding amount was not specified.

Other funding

In 2022, the D-SOLVE Consortium — a team of experts in HDV research from several European institutions (Germany, France, Sweden, Italy, Romania) — received a €6.75 million grant from the European Union to study and develop tailored treatment approaches for hepatitis D. This will involve research to understand the variation in viral suppression across individuals, mechanisms of disease progression, and response to antiviral treatment.

Gilead Sciences launched the ALL4LIVER grant program in 2021 and has awarded >$1 million in grant funding directed at initiatives to combat hepatitis B, C, and D. The initial 2021 launch was specific to the Asia-Pacific region, but in 2023, Gilead expanded the program to support countries around the world excluding the United States. 71 projects were funded in 2023. About half of the funded projects focused on either HBV or HCV, and five projects addressed gaps in HBV, HCV, and HDV.

Similarly, Gilead’s SPEARHEAD program, launched in 2022 in the U.S. and relaunched globally in 2024, will provide grants of up to $200K for programs aimed at understanding and addressing barriers to HDV screening and linkage to care.

Tractability

In this section, I suggest ways philanthropic funds could address the burden of HDV by addressing the challenges I described earlier.

John W. Ward, director of the Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination (CGHE), said that improved prevalence data would draw the needed attention to HDV and motivate policy change. Proper estimates of the HDV burden and its contribution to liver disease, both globally and across countries, would provide a clearer picture of its true impact, and help direct attention and resources. While higher estimates could drive urgency, government and other donor efforts, and policy action, lower estimates could refine priorities and ensure proper allocation of resources.

Summary of BOTEC methodology (full calculation here):

- I assume a grant amount of $1.5 million, which would pay for both the HDV prevalence study and the cost of follow-on engagement with relevant government stakeholders in Nigeria (which has a high burden of HBV).

- Of the ~471K DALYs due to chronic HBV infection in Nigeria, I estimate ~63K DALYs due to HDV.

- I assume an 80% probability that the study will be conducted successfully and a 10% probability that the study results will influence government policy action and investment in HDV.

- I assume that the increased government attention will address 20% of the DALY burden in the country.

- I apply a five-year speed-up (i.e. assuming that the grant enables the collection of improved prevalence data five years earlier than would otherwise happen). This results in an estimated 5,017 DALYs averted and an SROI of 334x.

- I apply a downward adjustment of 10% to account for the contribution of government resources to reducing the burden.

This gives a final SROI of 301x — very far below our bar of roughly 2000x.

The availability of a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) could encourage uptake of WHO-recommended reflex testing for HDV and improve surveillance. Palom et al. 2022 and Cossiga et al. 2024 reported improved screening rates and increased identification of individuals with HBV/HDV coinfection following the implementation of reflex testing.

A rapid diagnostic test for anti-HDV screening was highlighted by experts as an area that would significantly and positively impact the HDV space. Current diagnostic methods for HDV are laboratory-based, as mentioned in the “diagnostic challenges” section. This limits the scale-up of HDV diagnosis in LMICs, and an expert from CGHE mentioned that improved access to diagnostics would be an important first step in addressing the burden of HDV in LMICs.

One argument against making this grant would be that improved testing without addressing barriers to treatment will not reduce the burden of HDV. However, a small fraction of those diagnosed may be able to access treatment. Others who test positive for HDV might adopt other positive health behaviors. Better epidemiological data on the burden of the disease could improve impact modeling and lead to stronger advocacy for access to treatment, which could in turn spur action from governments and other donors.

The current WHO guidelines stipulate HBV/HDV coinfection as an indication for commencement of HBV treatment (without the requirement of other tests like HBV viral load or liver function tests). Improved access to HDV testing could simplify the process of treatment initiation for hepatitis B.

Summary of BOTEC methodology (full calculation here):

- I assume a grant of $2.5 million that supports the field testing and commercialization of a rapid diagnostic test for HDV.

- This figure is partly based on quotes we’ve heard for similar projects while investigating other health conditions.

- I estimate the DALY burden of HDV in LMICs to be ~2.5 million DALYs (after applying CG’s standard downward adjustment to the GBD DALYs estimate).

- I assume that the RDTs would improve HDV screening rates from a baseline of 3% to 10% — a 7 percentage point increase.

- Buti et al. (2023) demonstrated that “reflex testing” for HDV (automatically testing anyone who tested positive for HBsAg) reduces the clinical and economic burden of viral hepatitis. Key points:

- HDV testing rates for people who tested positive for HBsAg rose from 7.6% to 100%, an increase of 92.4 percentage points.

- Treatment rate upon HDV diagnosis was 66%.

- Burden from HDV (liver complications) was reduced by 35-38% (midpoint estimate = 36.5%).

- Using the numbers above, for every 1% increase in HDV testing, treatment rate increases by 66/92.4 = ~0.71%.

- This is a simplified estimate; the linearity estimate might not hold. For example, early gains from testing might disproportionately reach engaged patients who are likely to obtain treatment, while further gains reach patients who are less likely to do so.

- Because the study took place in Spain, and people in LMICs typically have lower access to treatment, I apply an 80% reduction: 0.7 * (1 – 0.8) = 0.14.

- Based on the study, I assume that for every 1% increase in access to treatment, HDV burden (liver-related complications) is reduced by 36.5/66 = ~0.55%.

- I assume a 25% probability that the grant will lead to successful field testing and approval of an RDT for HDV.

- I assume a 30% probability that the developed RDT will be adopted and scaled up in LMICs.

- I assume a five-year speed-up due to the grant.

This results in an estimated ~20K DALYs averted and an SROI of 789x.

It might be possible to make grants to market shaping organizations to expand access to promising treatments that are currently under testing. One example is lonafarnib: a Phase 3 D-LIVR study tested the efficacy of lonafarnib combined with ritonavir, with or without PegIFNα, for 48 weeks among 407 patients. The combination therapy had higher efficacy — 19.2% of patients reached the primary endpoint of ≥2 log reduction in HDV RNA and ALT normalization, compared to 10.1% for lonafarnib + ritonavir and 9.6% for PegIFNα alone.

The LOWR-6 study, which also evaluates the efficacy of lonafarnib + ritonavir, is ongoing. If it is shown to be effective and gets regulatory approval, we could fund an organization to engage with the innovator and facilitate generic access for LMICs.

Summary of BOTEC methodology (full calculation here):

- The previous BOTEC assumed an improvement in diagnosis with treatment access in LMIC to be the same as if the treatment was PegIFNα. In this case, I assume simultaneous improvement in diagnostics and better access to an oral-based treatment (“the drug”).

- The BOTEC structure is the same as above, except for the following modifications:

- Additional costs: I assume minimal funding (a grant of $100K) to push for access conditions/generic licensing for the drug.

- Improved testing rates as HCWs will likely be more inclined to screen for HDV with the knowledge that more accessible treatment is available.

- I assume better treatment response with the drug.

- Because the study took place in Spain, and people in LMICs typically have lower access to treatment, I apply a 30% reduction (less than the 80% reduction in the previous BOTEC, since this opportunity would include efforts to facilitate access).

- Probability that the Phase 3 trial for the drug will be successful and lead to FDA approval (50%)

- Probability of favorable access conditions for the drug (70%)

- Probability that favorable access conditions will lead to significantly higher treatment rates in LMICs (40%)

This gives ~46K DALYs averted and an SROI of 1,773x.

Mother-to-child (vertical) transmission is the main mode of transmission of HBV, and infections contracted during infancy or early childhood progress to chronic hepatitis in approximately 95% of cases. Therefore, the WHO recommends that the HBV vaccine birth dose should be given as soon as possible after birth (ideally within 24 hours of birth).

The HBV vaccine birth dose costs ~$0.17-0.24 per dose. During our call with CHAI, they noted that Gavi’s support for introducing the hepatitis B birth dose in eligible countries is a welcome step forward. They emphasized further that additional support is needed to help countries sustainably integrate the vaccine into maternal and child health platforms within health facilities, and to develop context-specific strategies to reach women and newborns outside health facilities. These efforts would significantly reduce the burden of HBV, and HDV by extension.

Challenges to HBV vaccine uptake include poor awareness, out-of-facility births, supply chain issues, a shortage of trained health care workers, absent or poorly implemented strategies for national coverage, and a lack of access to health care facilities.

The grant would pay for technical support to the government to expand access to HBV vaccines.

Summary of BOTEC methodology (full calculation here):

- I assume a grant of $2 million. This would pay for an intervention to improve the uptake of birth dose vaccination in selected countries: Ethiopia, Malawi, and Nigeria.

- I estimate the 2021 DALY annual burden from chronic HBV infection for those countries.

- Based on modeling estimates by Nayagam et al. (2016), I estimate the share of reduction in mortality accounted for by increased coverage of hepatitis birth dose vaccination, and the relationship between mortality reduction and increased coverage.

- I assume an increase in vaccination coverage due to the intervention (from 18% to 30%).

- I calculate the mortality reduction due to the intervention, and deaths averted. Using CG’s standard figure of 32 DALYs for each premature death, this gives ~37K DALYs averted.

- I assume a 50% likelihood that the intervention will be successful and a three-year speed-up.

This results in an SROI of 1,833x.

Other opportunities in this space

- Support R&D to develop a cure for hepatitis B. Since HDV requires hepatitis B for replication even after infection, complete clearance of HBV will eventually clear HDV.

- Support the launch of a fund for hepatitis broadly: the field is neglected, there are tractable opportunities for existing interventions, and future products (like a cure for HBV or vaccine for HCV) could be hugely impactful.

- Awareness campaigns calling for health care workers to screen for hepatitis D, similar to the work of Hepatitis Delta Connect. This seems relatively unpromising: even if awareness is raised, barriers to diagnosis and treatment still exist.

- Market shaping to drive down the costs of current diagnostics and treatments for HDV. This is also not very promising, because the current price points are quite high and it will take a long time for prices to reach affordable levels in LMICs.

Conclusion

Overall, hepatitis D appears to be highly neglected. Arguably, the most tractable approach would be to improve HBV vaccination rates, especially birth dose vaccination. This, coupled with other HBV prevention interventions such as maternal prophylaxis and wider testing and treatment, will reduce the prevalence of HBV and in turn HDV.

These strategies, however, will not address the mortality and morbidity associated with those already coinfected with HBV and HDV. Despite the existence of barriers to prevention, testing, and treatment, there are tractable opportunities in this space. Additionally, since promising treatments could become available in the near future, it seems valuable to lay the groundwork for access to those treatments by improving diagnostics, and by using market shaping to ensure these treatment(s) will be affordable when they become available.

I am most excited about funding directed at accelerating the commercialization of RDTs for HDV (or better, a combined RDT for HBV and HDV) and LMIC access for the most suitable treatment options. Since two RDTs for HDV are in advanced stages, a philanthropist could engage with the developers to understand what it will take to bring the test to market.

From our conversations with experts, it seems unlikely that additional funding will speed up the process to get lonafarnib approved if the Phase 3 trial results are promising. Market analysis and preparation for accessing the product when available will help improve outcomes, in combination with the development of an RDT, and point-of-care testing for HDV RNA. I did not spend much time investigating other promising treatments in the pipeline, such as Pegylated Interferon Lambda and Nucleic Acid Polymers (NAPs). This is because issues with pricing and administration will likely make them unsuitable for LMICs for at least the next decade.

One obstacle to progress is that multiple changes need to happen at or around the same time to produce impactful reductions in the DALY burden from HDV. If, for instance, RDTs are developed successfully and priced comparably to existing RDTs, development of effective treatment may lag behind. This would result in a situation where individuals with HDV are successfully diagnosed but have no clear path to obtain treatment.

Additionally, despite the availability of rapid diagnostics for HBV, and relatively affordable treatment, testing and treatment coverage remain sub-optimal in LMICs. It could be more beneficial to first address the barriers to HBV diagnosis, as testing for HDV begins with an initial screening for HBV (though an RDT could also be developed that tests for both HBV and HDV).

Increased testing for HDV has the potential to draw more attention to HDV by showing that prevalence is higher than previously estimated. On the other hand, if it shows that the burden is much lower than previously estimated, that would still be valuable — it could help donors decide to focus attention on other, more promising areas.

Appendices

Resources

- WHO global hepatitis report (2024): pages 42 to 48 contain guidance on testing and treatment for HBV and HDV

- WHO guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis, care and treatment for people with chronic hepatitis B infection, March 2024

- 2024 study by the Polaris Observatory Collaborators which provides an adjusted estimate of the prevalence of HDV

- Global HDV Elimination: Challenges and Opportunities: July 2023 webinar hosted by the CGHE (Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination) and ICE-HBV (International Coalition to Eliminate HBV)

- 2024 Update on Chronic Hepatitis D: from Disease Awareness to Therapeutic Opportunities: July 2024 webinar hosted by the CGHE (Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination) and ICE-HBV (International Coalition to Eliminate HBV)

Interviews conducted

| Organization | Interviewee(s) + notes | Topics covered |

| Unitaid | Ferris Danielle, Eleveld Jan Akko, Barrett Kelsey, Timmermans Catherina Maria | Unitaid’s hepatitis strategy |

| Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination | John Ward, Gibril Ndowe | HDV epidemiology, barriers to addressing disease burden, promising strategies/products/interventions |

| Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) | Oriel Fernandes | HDV epidemiology, barriers to addressing disease burden, promising strategies/products/interventions |

| Saint Louis University | John Tavis | HDV virology, promising strategies/products/interventions |

| Stanford University School of Medicine | effrey Glenn | HDV epidemiology, barriers to addressing disease burden, promising strategies/products/interventions |

| World Health Organization | Niklas Luhmann | WHO’s hepatitis strategy |

| Virology Department at the Centre Pasteur of Cameroon Institut Pasteur, Cameroon | Richard Njouom | HDV epidemiology, diagnosis, and management in LMICs |

| German Center for Infection Research | Stephan Urban | HDV virology, promising strategies/products/interventions |

| Hospital General Universitari Valle Hebron, Barcelona | Maria Buti | HDV epidemiology, diagnosis, and management in LMICs |